5 Niles Center Becomes Skokie

By the late 1930s, some residents of Niles Center were beginning to campaign for a change in the village’s name. One reason expressed was that there was often confusion caused by the names of the two neighboring villages, Niles and Niles Center, both of which are within Niles Township.

Those who wanted a name change also pointed to neighboring Tessville, which in 1935 changed its name to Lincolnwood after the main street in the town and in recognition of the many wooded areas then within its village limits. Some Niles Center residents also noted that there had been a resurgence of residential construction in Lincolnwood shortly after the new name was adopted.

A number of real estate agents objected to what they deemed the old-fashioned rural quality of the name Niles Center. Prospective residents, they claimed, were reluctant to move to a village whose name conjured images of farmlands and country stores.

On the other hand, it was also clear that sentiment for a change was far from universal. Many longtime inhabitants of the village, especially those who lived in the vicinity of Oakton and Lincoln, considered any name change whatsoever an insult to the history of the community. They made their feelings known and set the stage for a baffle against the name change, although the baffle never did take place.

In response to the calls for a new name, Martin “Scotty” Krier, a director of the Chamber of Commerce, formed a committee in 1939 to solicit name suggestions from the village citizenry. A contest was sponsored, widely reported in the north suburban newspaper, The News, that same year. In the contest, as it was later reported, not a single suggestion bore the name Skokie, which, as it turns out, was erroneous.

More than 1,000 different names were submitted, many of them Scottish in nature and taken from a popular series of novels at the time. The Scottish names drew particularly poor reviews from many residents who were aware that the village roots had been implanted by the Germans and Luxembourgers.

The list was narrowed to 25 names for further consideration, which, as Richard J. Witty noted in his published history, Luxembourg Brotherhood in America, “the front page of the December 7, 1939 issue of The News lists ‘Skokie’ as among those nominated for the Village’s new name.

Topping the list, however, were the clearly unethnic names of Oakton and Ridgeview. In an informal run-off vote sponsored by The News, Ridgeview topped Oakton by 1,089 to 890 votes.

Despite the victory for Ridgeview, village trustees were not enthralled with the name. On a vote taken March 19, 1940, the village council voted 4-2 against a petition seeking to formalize the change. Two additional petitions were then filed, one asking for no name change at all, the other calling for a change to anything but Ridgeview. To settle the dispute, Village Mayor George E. Blameuser and the council called for a village-wide referendum to be held during the next scheduled election in June of 1940, in which residents would be asked whether the village should, or should not, change its name.

The referendum caused considerable interest. Lively debates were held in local newspapers, circulars were distributed door-to-door, and a street demonstration was held the night before the election. Over the opposition of many traditionalists in the village, the referendum to change Niles Center’s name passed by a relatively small margin.

“The old-timers could have won easily,” George Blameuser was quoted as saying by The Life newspaper, “if they had been better organized and hadn’t felt they were beaten before the election.” Blameuser also used the occasion to deny reports that the name change had been prompted by the unsavory reputation Niles Center had earned for its many speakeasies during the Prohibition era. “Of course we had them, everyone did,” he observed, “but Niles Center couldn’t hold a candle in this area to some of its faster neighbors.”

Whatever the reason, the June referendum merely approved a change in the village’s name. A committee of about 30 residents, including village trustees and other civic leaders, was then appointed to come up with a name. One of the people on the new committee was Armond D. King, who had organized the village’s Planning and Zoning Commissions and served as chairman of both for many years. King, a real estate agent who had been active in the community since 1926, had originally opposed the referendum to change the village’s name, but now that it was passed, he was determined to make the best of the situation.

Like other members of the Planning Commission, King knew that Cicero Avenue within the village limits was being renamed Skokie Boulevard, prompted, no doubt, by the nearby Skokie Lagoons, which had been so named by the federal government. The name, of course, was hardly unknown in the area.

The Skokie River flowed just north of Niles Center, and the North Shore railroad was known as the Skokie Valley branch. Niles Center’s motto, in fact, was “Gateway to the Skokie Valley.”

As the story goes, while working at his desk one morning, King noticed a letter from Boston’s Shawmut National Bank, whose letterhead included a portrait of a Potawatomi Indian. Remembering that the Potawatomi long ago had called the Niles Center area Skokie, for “big swamp,” King appreciated the historical significance, and apparently remembered its earlier suggestion to Scotty Krier’s committee and its qualification among the 25 name finalists in 1939.

King cut out the portrait from the letterhead, pasted it on an envelope, and added the words “Skokie, Illinois.” He showed the envelope to Willard Galitz, the son of Niles Center Bank founder William Galitz. At the time, Willard was a cashier at the Niles Center Bank and later served as president of the rechartered First National Bank of Skokie. Galitz agreed that the suggestion was a good one.

In the meantime, the 30-member “name committee” had been struggling to fulfill its duties. Among the names it had been considering were Oakton, Ridgemoor, Woodridge, and Westridge. The name Skokie was suggested during the latter stages of the talks. “It was just batted out during one of our informal discussions,” George Blameuser recalled.

Strongly backed by King, Galitz, and others, the name Skokie prevailed, receiving 15 of the 24 votes cast by members of the committee. Of the also-rans, Oakton received 4 votes, Woodridge 2, Ridgemoor 2, and Westridge 1. The vote received little publicity, but the results were quick. On August 21, the new name was filed in Springfield and approved the next day.

Two weeks later, on September 5, 1940, a petition signed by about half of the voters in the June election was presented to the Board calling for the name change to Skokie. On October 1, despite continuing mild opposition, the Board voted in favor of the new ordinance, which became effective on November 15, 1940.

Some residents still resisted, however, keeping Niles Center prominent in the names of businesses and organizations for a few years. But eventually they gave in and the name Niles Center became merely a matter of historical interest.

In summation, Richard J. Witty observed appropriately in his Luxembourg Brotherhood of America, “If Scotty Krier initiated the name change, Armond King nurtured it, and George E. Blameuser implemented it.”

Looking down on Lincoln Avenue and St. Peters Church

Looking down on Lincoln Avenue and St. Peters Church

The War Years

In the years leading up to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s involvement in World War II, the elements of nature brought a sense of foreboding to the village of Skokie of the turmoil that was to come. In July 1938, an intense rain storm caused severe flooding along the North Branch of the Chicago River. About six months later, on January 30, 1939, a snowstorm swept inland from Lake Michigan and dumped 14 inches of snow on the village.

Then, in February 1941, the first taste of the looming war came when 11 men from the Park Ridge district, which included Skokie, were inducted into the army.

Not all signs during the prewar years were so ominous, however. On April 16, 1939, the new Niles Township High School building on Lincoln Avenue was formally dedicated.

Other news in the village in 1941 included these positive items. The value of construction totaled more than $3,000,000. In June, work was started on the $390,000 G.D. Searle pharmaceutical plant at Niles Avenue and Searle Parkway. Later that month Washington postal officials accepted Clara Blameuser’s bid to construct a new post office building at 4915 Oakton. The roots of Skokie’s modern public library took hold the same year when, on November 4, villagers approved a referendum to support it with public taxes.

In the first week of December 1941, residents first learned of plans for the proposed Edens Expressway, which would require the demolition of homes along the right-of-way and skirt the village limits of Skokie, making automobile travel between the village and Chicago easier than ever before.

The clear signs that Skokie was about to begin a boom were halted suddenly, however, on December 7, 1941. And it struck home swiftly when, during the air attack on Pearl Harbor, Gordon Mitchell, a resident of Skokie before he had enlisted in the armed services, was killed. America officially entered the war the following day. Village President George E. Blameuser, in his capacity as coordinator of the Skokie Defense Council, issued emergency instructions to village departments and appointed Trustee Ambrose Brod to act as blackout warden to prepare villagers for possible nighttime air raids. By March 1942, 140 village air raid wardens met with Chief Brod to formalize Skokie’s defense plans.

On January 9, 1942, The News received word that a Skokie resident, U.S. Marine PFC Robert G. Woodburn, was killed while in training in San Diego. Woodburn was officially recognized as the township’s first casualty of World War II because Gordon Mitchell had been killed before the United States had formally declared war.

One of the village’s most important events during the war years occurred March 9, 1942, when Chicago’s G.D. Searle pharmaceutical company moved its new headquarters to Skokie. By the 1980s, the company would employ nearly 2,000 workers.

In one way or another, however, most residents of the village felt the effects of the war. Even those not inducted into the military found the wartime economy vastly different.

Members of the Woman’s Club of Skokie sold war bonds and stamps, operated area canteens, performed voluntary Red Cross work, and worked on projects to conserve food. When the federally organized Rationing Point Program went into effect March 1, 1943, residents of Niles Township lined up to register for war ration books.

During the summer of 1943, the Skokie village government supplied tractors free of charge to plow up land for area Victory Gardens. Many village residents planted such gardens, a task quite reminiscent of the village’s roots as a truck farming and greenhouse community.

After nearly four years spent supporting the war effort, all businesses in the village were closed to celebrate VJ Day in 1945. The deprivations of the war years, following those of the decade-long Depression, were nearing an end. Skokie was about to enter its second, this time sustained, period of growth.

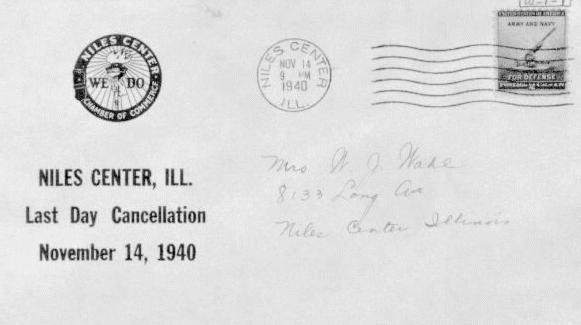

Last day cancellation for Niles Center, IL

Last day cancellation for Niles Center, IL

Last day cancellation for Niles Center, IL

Last day cancellation for Niles Center, IL

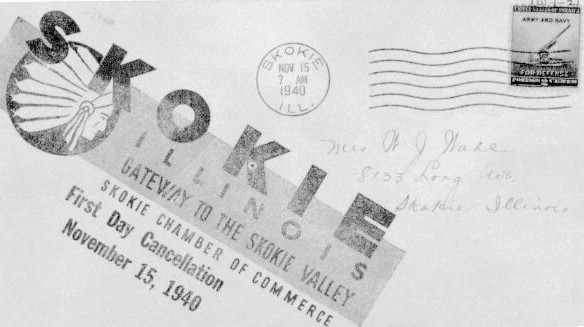

First day cancellation for Skokie, IL

First day cancellation for Skokie, IL

The Postwar Boom

During the first real estate boom, which occurred in the 1920s, village planners saw Skokie developing much along the lines of neighboring Evanston and accordingly zoned much of the land to be developed for apartment buildings. But as villagers turned their thoughts from World War II to their own neighborhoods, it became clear that Skokie, at least in the near future, was not destined to follow Evanston’s lead. A conscious decision was made to try to preserve the village’s suburban, single-family residence quality.

In May 1946, the Board of Trustees adopted the Skokie Village Master Plan, basically a rezoning ordinance, which shifted the emphasis on new construction from apartment houses to single family residences. It was a wise choice. Not only did the new ordinance help to set Skokie apart from Chicago and Evanston, but it also laid the groundwork for decades of sustained growth.

During the years following World War II, the empty lots north of the downtown buildings, so evident in aerial photographs from the 1930s, began filling up with family homes. Statistics aptly describe the story. In 1945, 124 new homes, with a combined value of just over $1 million, were constructed within the village limits of Skokie. Just nine years later, in 1954, the number increased more than tenfold. A total of 1,554 homes were built that year alone, valued at about $24.5 million.

The village’s population increased from 7,172 in the census of 1940 to 14,752 in 1950. A special census completed in early 1954 indicated that the population had swelled to 23,704, more than the combined populations of neighboring Morton Grove, Lincolnwood, Niles, and Golf. Eight years later, in 1962, the population of Skokie passed the 65,000 mark.

Part of the reason for the rapid growth during the 1950s was the construction of Edens Expressway. Dedicated October 8, 1949, and opened on December 20, 1951, the highway and its familiar access ramps at Dempster gave area residents easy entry to the principal automobile route between Chicago and the northern suburbs. For several years during the early 1950s, Skokie was the leading homebuilder of all Chicago’s suburbs.

During the postwar decade, officials in village government had to work hard to keep local services at a pace with the explosive population growth. In 1948, the Village Board approved construction of a new firehouse and voted to repair the Floral Avenue station, and authorized various oversight boards to begin staffing the fire department with paid, full-time employees.

In 1949, the trustees approved a 25-year contract to purchase Lake Michigan water from the city of Evanston, a plan that became a reality in 1952.

By 1953, the Village Board passed Skokie’s first million-dollar appropriations measure for the fiscal year ending April 30, 1954. And, on July 19, 1955, the Board voted to impose a five percent sales tax on most items sold within the village limits, with the new tax effective on September 1 of that year.

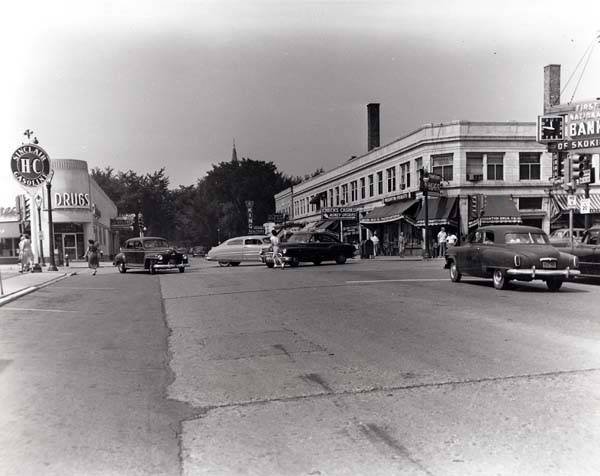

Downtown Skokie in the late 1940s, looking west along Oakton from Lincoln.

Downtown Skokie in the late 1940s, looking west along Oakton from Lincoln.

Niles Township High School as it appeared on the cover of Skokie Life on March 6, 1941, which, incidentally, cost a nickel in those days.

Niles Township High School as it appeared on the cover of Skokie Life on March 6, 1941, which, incidentally, cost a nickel in those days.

The Jewish Migration

Many of the people who came to Skokie during the postwar era moved from apartment houses in Chicago. But unlike the earlier migrations to Niles Center, these newcomers consisted of large numbers of Jewish people, many of Eastern European heritage. During the decade from 1945 to 1955, approximately 3,000 Jewish families settled in Niles Township, many within the boundaries of Skokie.

Before long, a variety of Jewish community organizations were formed by the new arrivals, including the Niles Township Jewish Men’s Club in 1949, the Niles Township Jewish Community Club in 1950, and the National Council of Jewish Women in 1953. The Niles Township Jewish Community Club formed the nucleus of support for the township’s first synagogue.

The Niles Township Jewish Congregation, under the spiritual leadership of Rabbi Sidney Jacobs, held the first Jewish service in Niles Township on May 18, 1952, at the Skokie Village Hall. Congregation Bnai Emunah, with Rabbi Melvin Goldstine serving as its spiritual leader, was founded about two years later. By 1955, membership in the Niles Township Jewish Congregation was more than 400, and the conservative congregation Bnai Emunah numbered more than 350. A third congregation, reformed Temple Judea, was organized in 1954 and met, temporarily, at the Lincoln School. In 1955, all three congregations had blueprints for new synagogues.

Growth of Community Groups and Businesses

During this same era, a great many other community organizations were founded as well, reflecting the explosive growth of the village. The Skokie Council of the Knights of Columbus, Skokie Masonic Lodge Number 1168, and the Skokie Valley Council of Parent-Teacher Associations were all formed in 1949. The Junior Women’s Club was founded in 1950. In 1951, the Garden Club of Skokie, Niles Township High School PTA, the Loyal Order of Moose Skokie Lodge No. 376, and the Skokie Valley Community Concert Association all became part of the community.

The first Niles Township Community Chest campaign was conducted in 1952, and the League of Women Voters of Skokie, (later renamed the League of Women Voters of Skokie-Lincolnwood), was established in 1953. In a burst of civic activity in 1954 came Congregation Bnai Emunah Sisterhood, Skokie Business and Professional Women’s Club, Skokie Valley Kiwanis Club, and the Toastmaster Club of Skokie.

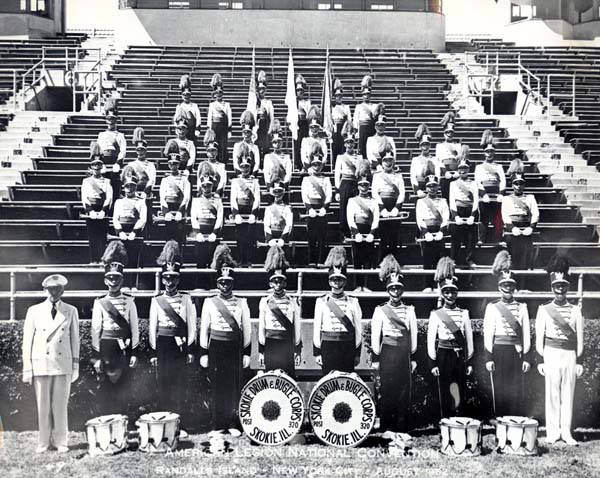

On October 10, 1955, the Skokie Indians Drum and Bugle Corps, sponsored by American Legion Post 320, won the first of an unprecedented three consecutive national championships in competition at the Orange Bowl in Miami, Florida. That same year, the Skokie Valley Chapter of the YMCA was chartered.

In the early 1950s, Skokie remained one of the largest truck farming areas in the United States. But the character of business and commerce was rapidly changing. Growing right along with the dramatic population increase and the swelling ranks of civic organizations were the numbers of non-agricultural businesses that moved to the village during the postwar decade.

Among the significant of the new businesses taking up residence in Skokie were the Teletype Corporation, (which soon became the village’s largest employer), the W.M. Welch Manufacturing Co., and the national headquarters of Rand McNally & Co., book publisher and map maker, arriving in 1952. Following them was the Illinois regional office of Allstate Insurance Company in 1953.

By 1954, a total of 296 retail establishments were operating within the village limits. The number increased dramatically just a few years later when the Old Orchard Shopping Center, first announced in 1950, was completed in 1956.

Jubilation at Civic Party headquarters in April 1959 after election victory; clasping hands are, from left, Albert Smith, Ray Jackson and Bill Siegel.

Jubilation at Civic Party headquarters in April 1959 after election victory; clasping hands are, from left, Albert Smith, Ray Jackson and Bill Siegel.

The renowned Skokie Drum & Bugle Corps at the American Legion National Convention at Randall’s Island in New York in 1952

The renowned Skokie Drum & Bugle Corps at the American Legion National Convention at Randall’s Island in New York in 1952

Skokie Comes of Age

During the 1950s and early 1960s, a series of governmental scandals and subsequent reforms eventually transformed the administration of Skokie into a model of suburban government, led by a professional village manager and a multi-term mayor, Albert J. Smith.

The period also saw the completion of two new high schools, a new post office, a magnificent public library building, a village court system and the Skokie Swift rapid transit system. During that time, the village also celebrated its diamond jubilee, and received official affirmation that Skokie was indeed the “World’s Largest Village.”

The continuing explosive population growth of Skokie and Niles Township made unprecedented demands on local services, however. By the fall of 1955, a record-shattering total of approximately 19,000 students were attending public schools in the township. Fortunately a much-needed second high school was already under construction. A $300,000 bond issue had been passed in August 1954 for the purchase of 56 acres of land at Oakton and Major for the new school. Ground-breaking ceremonies were held May 15, 1956, about six months before Old Orchard Shopping Center opened.

Another ceremony to break ground for Oakview Junior High School was held July 28, 1958, a little more than a month before Niles Township High School West was officially opened for the fall school year.

The year 1959 was pivotal for the village’s government. At the beginning of the year, on January 20, residents opposed a plan to change Skokie’s status from a village to a city, thus ensuring the at-large election of trustees. In the election held April 7, the Caucus Party overwhelmed the Democratic-Republican United Party, putting the voters’ stamp of approval on the relatively new village manager form of government.

The census of 1960 indicated that Skokie’s population was 59,364. But well before all heads were counted, on February 1, 1960, the Skokie Public Library’s award-winning new building was opened. Six days later, villagers voted overwhelmingly in favor of building a third high school, Niles Township North, although funding was not approved in a referendum until more than a year later. A new building for the Skokie Post Office, at 4950 Madison, was dedicated in October.

A few months later, in June 1960, voters approved a plan to create a court of record with jurisdiction over certain legal matters within the village limits (others were reserved for the Circuit Court, which had a more expansive venue). The resolution called for the creation of two village judgeships and the office of court clerk. In elections held in December, Irving Goldstein and Harold Sullivan were elected to judgeships and Shirley Neuman was elected clerk, all three- to six-year terms. In January 1961, court sessions began on the second floor of police headquarters at Lincoln and Main.

Skokie’s first radio station, WRSV-FM (the call letters stood for Radio Skokie Valley), began broadcasting in July 1961. Less than a month later, a study published in the Skokie Review revealed that there was a total of 11,733 single family homes in the village, 571 two-fIat apartments, 118 three-fIats, 397 co-ops, and 164 townhouses.

In a fast-growing community of such diverse cultural interests, it is not difficult to imagine controversy arising from time to time. One such situation arose during the holiday season of 1961 when there was an unseasonably heated disagreement over the construction of a Nativity scene on village property along Oakton Street just west of the Village Hall. The Board of Trustees eventually eased the tension by passing an ordinance allowing anyone to put up a display celebrating anything on village property.

In December 1961, the “pin-up” picture of 85- year-old Alma Louise Klehm, Niles Center’s pioneering school teacher, appeared as the cover girl on the First National Bank’s calendar. The year covered by that now locally famous calendar saw the creation of the first Skokie Historical Society (the society that exists today was not founded until 1978) as well as the Skokie Valley Symphony Orchestra.

Ambrose Reiter, who served as a Village Trustee (1949-57) and Mayor (1957-61) addresses a voters’ group in 1957.

Ambrose Reiter, who served as a Village Trustee (1949-57) and Mayor (1957-61) addresses a voters’ group in 1957.

A ribbon-cutting ceremony at the dedication of the new Skokie police headquarters at 8333 Lincoln Avenue: left to right: Jack Seeley, Ray Krier, Ambrose Reiter, Jum Smith, Mrs. Wilson, Bill Krewer, Police Chief William Griffin

A ribbon-cutting ceremony at the dedication of the new Skokie police headquarters at 8333 Lincoln Avenue: left to right: Jack Seeley, Ray Krier, Ambrose Reiter, Jum Smith, Mrs. Wilson, Bill Krewer, Police Chief William Griffin

Skokie Comes of Age

In April 1962, the board of trustees adopted a new slogan for Skokie: “Village of Vision.” But the motto was to be short-lived, replaced as the result of a revelation that came a few months later. Back in the 1920s, it may be recalled, a series of substantial annexations gave Niles Center the largest area of incorporated land in the United States administered under the village form of government. Nearly 40 years later, on June 26, 1962, the Board of Trustees noted that the population of Skokie had surpassed that of Oak Park, Illinois, by about 4,200 residents, thus giving it the largest population of any village in the United States.

At that point, the trustees proclaimed Skokie as “The World’s Largest Village.” The official motto may still have been “Village of Vision,” but not long after the trustees’ proclamation, the phrase “The World’s Largest Village” began appearing in newspapers and brochures and on signs strategically located at various village boundaries.

A little more than a month after the designation of Skokie as “The World’s Largest Village,” the citizenry began a year-long Diamond Jubilee Celebration, marking 75 years as an incorporated village. The pageant culminated with a major parade from Old Orchard Shopping Center past a reviewing stand near Niles Center Road and Oakton on July 20, 1963.

In an agreement with the federal government, the Village Green, on Oakton Street just west of Village Hall, was officially declared as Open Space in 1964, opening it to the public for any lawful use. The contemporary sculpture by John David Mooney, which graces the Green, was commissioned by the village and unveiled in 1978.

It was a festive time, both for private residents as well as resident businesspeople. By 1964, Skokie had about 900 retail businesses with combined annual sales of more than $175 million. The village’s 350 industries produced nearly $1 billion worth of products.

The World’s Largest Village

Despite the fact that Skokie Valley was one of the fastest growing areas in the United States throughout the 1950s, none of the communities within its general boundaries had a hospital until late in 1963. That was the year in which the Skokie Valley Community Hospital was officially dedicated. The event marked the end of a nearly decade-long campaign to build a major health facility in the area.

Back in the middle 1950s, many residents of Skokie and neighboring communities recognized the need for a local hospital. Around 1954, two men took the lead in channeling that interest in a constructive direction. One was Dr. Raymond Gait, a resident of Golf who became chairman of the hospital’s building campaign committee, and the other was Thomas H. Coulter, executive director the Chicago Association of Commerce and Industry. In December 1955, the village trustees obtained an Illinois state charter for “Old Orchard Community Hospital,” whose name was changed to Skokie Valley Community Hospital three years later.

In 1956, the present hospital grounds, 16 acres of land at the intersection of Gross Point and Golf Roads in Skokie, was purchased from the Skokie Park District. During the next five years, more than $5 million in funds were secured for the project, more than half of which came in the form of contributions from major industries, companies, and area residents. The ground-breaking ceremony took place on December 2, 1961. A little less than two years later, on November 3, 1963, the hospital was formally dedicated.

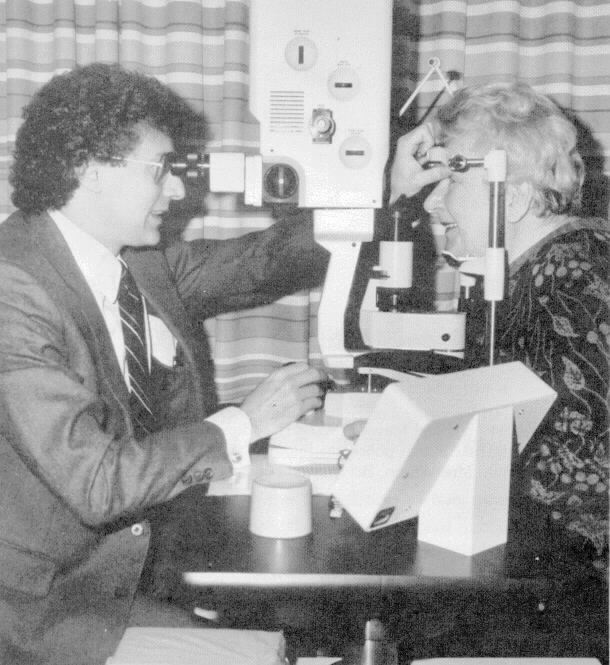

By the middle 1980s, the Skokie Valley Hospital had grown into one of the most important resources in the area.

In 1987, the hospital affiliated with Chicago’s prestigious Rush-Presbyterian St. Luke’s Medical Center and a rededication ceremony was held on August 9.

Renamed the Rush North Shore Medical Center, the hospital still specializes in short-term acute care. The 218-bed institution is staffed by approximately 400 physicians, more than 750 employees, and approximately 200 volunteers.

Its emergency department has physicians and nurses on duty around the clock. Facilities include a wide range of the most up-to-date diagnostic and therapeutic equipment, such as a state-of-the-art CT scanner and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Currently in the development stage are facilities for radiation therapy and cardiac catherization.

The staff also operates services that range from a “Careunit” for alcohol and drug abuse to the preventive “Good Health” and cardiac rehabilitation programs.

The eye treatment is being carried out in the Rush North Shore Medical Center’s ambulatory care unit.

The eye treatment is being carried out in the Rush North Shore Medical Center’s ambulatory care unit.

External view of the Rush North Shore Medical Center, formerly known as the Skokie Valley Hospital

External view of the Rush North Shore Medical Center, formerly known as the Skokie Valley Hospital

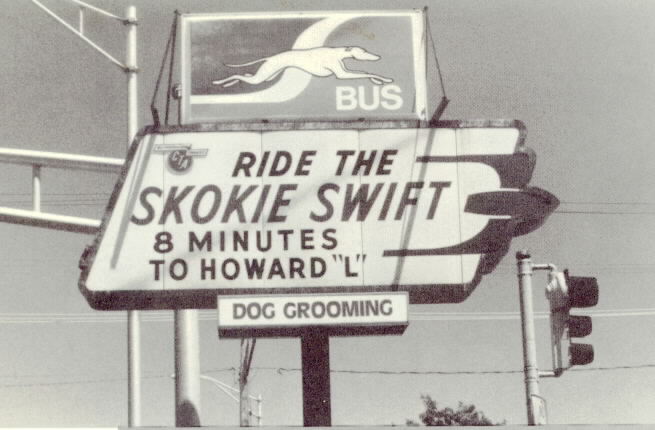

The Skokie Swift

For nearly four decades, the old Chicago, North Shore and Milwaukee Railroad had brought the convenience of Chicago’s Rapid Transit System to the residential neighborhoods of Skokie. On January 21, 1963, however, the railroad closed down, citing financial losses due, for the most part, to the popularity and convenience of automobile travel on Edens Expressway. For many residents of the village who preferred riding on elevated trains to driving, the event was a most unhappy one.

The inconvenience, fortunately, was one of only short duration. A little more than a year later, aided by grants from the United States government’s Department of Housing and Urban Development, the five miles of abandoned track between the old North Shore’s Dempster Street station and the Chicago city limits were rehabilitated and a high-speed commuter shuttle, dubbed the Skokie Swift, began operating.

Extensive modifications were made along the line. The stations at Main, Oakton, Kostner and Crawford were demolished. A paved parking lot, expanded several times, was added at the remaining station at Dempster Street. A number of improvements were made to the track and crossing gates at various points along the five-mile route. The electric railroad cars received their power from a combination of overhead trolley wires for the slightly more than two miles from Dempster to East Prairie, and from an electrified third rail from East Prairie to Howard Street.

Service on the Skokie Swift, operated by the Chicago Transit Authority, began in April 1964. By the early 1980s, about 3,600 people were riding the little line daily. Efforts by Chicago and regional transportation authorities to obtain federal grants to extend the line 1.8 miles to Old Orchard Shopping Center have been stalled by federal domestic spending cuts in the 1980s. “The Reagan administration posture on rail extensions is that they will not support them,” RTA planning director Joanne V. Schroeder said in 1981.

Despite the minor setbacks, the development of the Skokie Swift has helped thousands of commuters from Skokie and the immediate area. In 1965, American City magazine gave Skokie its “Award of Merit for Leadership” for the village’s role in the development of the rejuvenated line.

Notes From the 1960’s

A number of noteworthy, if varied, events occurred during the middle 1960s. On May 26, 1965, a tornado touched down and tore away almost all of the roof of Old Orchard Junior High School.

Little more than two months later, on August 2, the Board of Trustees directed the Board of Local Improvements to provide for the hard resurfacing of the last twelve miles of unpaved road within the village limits.

Early in 1966, Chicago and village newspapers reported that Skokie ranked second in the nation in terms of the number of telephones per capita. A study reported six years later in the Chicago Tribune of January 23, 1972, amplified the statistical oddity. The study showed that the four Chicago suburbs with Skokie’s exchange number were one of only three areas in the nation with more telephones than people. The other two were Washington, D.C. and Southfield, Michigan. The total population within the Skokie exchange was about 131,000, but there were 131,270 telephones, or 100.1 for every 100 people.

Also in 1966, the Leaning Tower YMCA, located on Touhy Avenue just west of Niles Center Road, was dedicated. Although it is not within the village limits, it still serves Skokie residents as well as people from neighboring villages. For travelers passing by, the scaled-down copy of the famous tower in Pisa, Italy, offers one of the more quaint sights in the Chicago area.

Besides the tornado of 1965, Mother Nature added another touch of inclement weather on January 26, 1967. A record-shattering blizzard struck Skokie and the entire Chicago area. Few who lived here during the now-infamous “Blizzard of ‘67” will ever forget the enormous snow drifts, the abandoned vehicles, and the peaceful, almost silent scene of an entire metropolitan area brought to a standstill.

Five months after that calamity, on June 10 and 11, violent thunderstorms caused massive flooding and destruction, and led to the creation of Skokie’s Flood Control Action Commission.

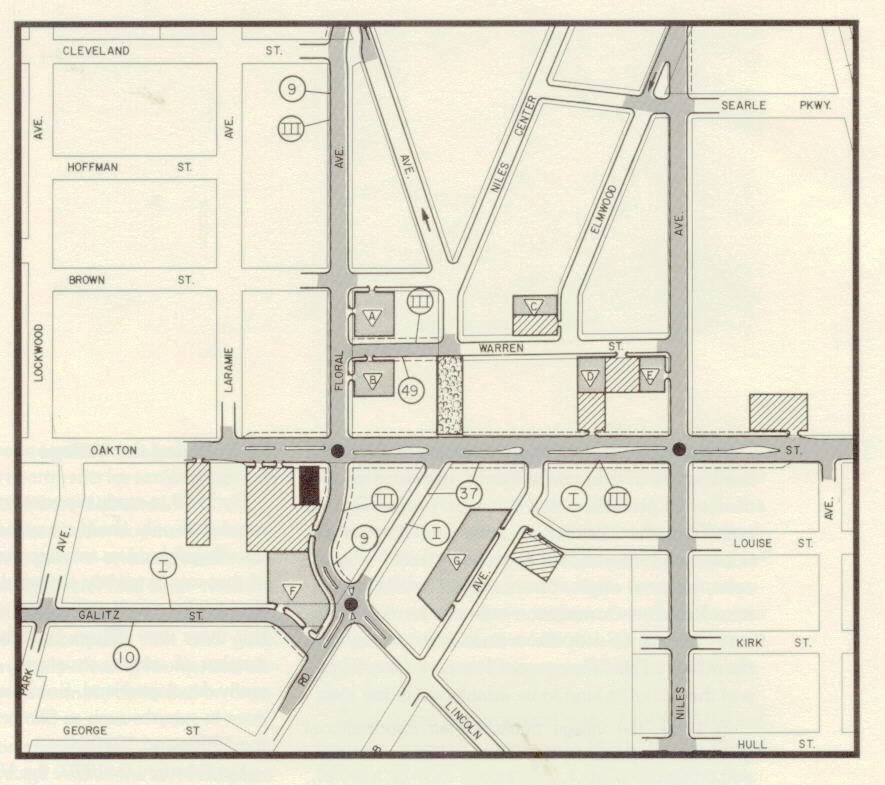

The layout of a proposed mall for Lincoln Avenue in the 1970s showing suggested changes which were never adopted

The layout of a proposed mall for Lincoln Avenue in the 1970s showing suggested changes which were never adopted

The Cook County Circuit Courthouse at 5600 Old Orchard Road, which officially opened its doors for legal business in early 1983

The Cook County Circuit Courthouse at 5600 Old Orchard Road, which officially opened its doors for legal business in early 1983

Human Rights

During the 1960s and early 1970s, nationwide protests against racial discrimination became nearly as fervent as demonstrations against the war in Vietnam. While unrest over unfair housing practices spread throughout much of the country, Skokie became one of Chicago’s first suburbs to pass a fair housing ordinance. The village’s first anti-discrimination housing law was passed in October 1967, and it was greatly strengthened in an amendment the following year.

The Skokie Fair Housing Ordinance of 1968, the first enacted in the state of Illinois, approved on December 2, prohibited discrimination by owners and realtors in the sale, rental, lease and financing of homes and apartments because of race, religion, color, national origin, or ancestry. The Skokie Human Relations Commission was also formed to ensure compliance with the ordinance as well as with the village’s Fair Employment Practices Law. It, too, was the first of its kind to be established in the state.

In 1966, the village published an informational brochure, prepared by the Skokie Human Relations Commission, entitled Your Home and Skokie’s Future. The 12-page booklet included the following analysis of the benefits of open housing policies in suburban communities:

“If members of minority groups are able to buy suburban homes in a free market and with full equality of housing opportunity, they can be easily absorbed, and in the normal course of events will find homes throughout suburbia in a pattern which approaches uniform dispersion. On the other hand, if their influx into the suburbs is resisted, particularly in widespread, organized fashion, their movement to the suburbs, while perhaps initially slower, will eventually form suburban ghettoes, with all their accompanying problems.”

Skokie’s sizeable Jewish population was also instrumental in improving awareness of the deplorable condition of human rights for Jews in the Soviet Union. In January 1971, the village board adopted an ordinance demanding freedom for Soviet Jews. The ability of Skokie’s Board of Trustees to influence Soviet domestic policies was, of course, limited, but a thoughtful voice had been heard and a clear point made.

Revitalizing the Village

By 1969, a study reported in the Skokie Life indicated that only about six percent of the land within the village’s borders remained vacant, and virtually all of that was in widely scattered lots. The amount of land left for new development was obviously limited. But there was still an opportunity to modernize a number of existing structures, and to rebuild on already developed land. Some aspects of urban decay, even in suburbs such as Skokie, were evident during the 1960s and 1970s.

On February 9, 1970, the Village Board was presented with a comprehensive plan, prepared by the Planning Commission, to regulate development and redevelopment in Skokie. A couple of major steps in the village facelift had already been in the works. On November 6, 1967, approval was given for the construction of the multi-million dollar Miller commercial complex at the southeast corner of Golf Road and Skokie Boulevard. A year later, on November 21, 1968, a building permit was issued to the Jewish Community Center of Niles Township to construct a facility on Church Street between LeClaire and Lawler.

Late in 1970, village planners released the details of a plan to revitalize the downtown business district. On May 3 of the following year, the village board formally adopted “Project Impact,” a comprehensive plan for improving the appearance of the downtown area.

Almost immediately, the First National Bank of Skokie (today known as the NBD Skokie Bank) took the lead in commercial redevelopment of the downtown area by announcing plans for a new bank building to be constructed at the intersection of Lincoln and Oakton. Construction began a little more than two years later. In the meantime, on June 25, 1971, the Armond D. King apartments for senior citizens, at 9238 Gross Point Road were dedicated.

A big boost for the area redevelopment came on August 12, 1971, when ground-breaking ceremonies were held for the Skokie Hilton Hotel (soon renamed the North Shore Hilton) at Skokie Boulevard and Golf Road. The hotel, complete with 368 guest rooms, seven contemporary meeting rooms, and elegant dining facilities, was formally dedicated on October 27, 1973.

Changing population patterns have caused a number of alterations in village institutions in recent years. Because of declining enrollment, a number of schools have closed: historic Niles East in 1975, Sharp Corner and College Hill a year later, Kenton and Cleveland by the mid-1980s, and scheduled for closing after the 1988 school year is Fairview North.

The Deep Tunnel Project

Like much of the Chicago area, Skokie has had its share of flooding problems over the years. The struggle to keep some areas dry during the spring and other times of heavy rainfall has been a consistent theme in the history of the village as well as much of Chicagoland.

On November 14, 1974, the Northeastern Illinois Planning Commission endorsed the massive, albeit controversial, North Shore Channel Deep Rock Tunnel, part of the even larger, more expensive Tunnel and Reservoir Plan (TARP) of the Metropolitan Sanitary District, a project popularly known as the “Deep Tunnel.”

The multi-billion dollar plan involved the construction of 110 miles of huge storm tunnels carved out of the limestone bedrock an average of 300 feet below the Chicago River, the North Shore Channel, the Sanitary Ship Canal, and the Cal-Sag Channel. Much of this project, with four times the carrying capacity of the surface river system, has been completed. A second phase, far from complete, involves the construction of an additional 20 miles of tunnel and three huge reservoirs, specifically created to alleviate flooding.

Since it was first proposed in the 1960s, TARP has been controversial. In the early 1980s, former Illinois Senator Charles Percy called it an “engineering pipe- dream” and “the granddaddy boondoggle of them all.”

During widespread flooding in the Chicago area in 1987, the Deep Tunnel failed to alleviate problems. Defenders point out, however, that the project is not yet complete and, at the time, it could not be expected to handle the vast amounts of surface water standing on saturated soil. But while the final verdict has yet to be delivered, other municipalities, including Milwaukee, San Francisco, and Rochester (N.Y.) are taking TARP seriously. All three have similar plans.

Flood Control

Flooding in homes and businesses had posed a major problem for the residents of Skokie for many years. It was the heavy rains and flood damage in the summer of 1981 that forced village officials to launch an all-out attack on the problem.

The problem emanated from the sewer systems that had been constructed in the 1920s. They were combined sewers intended to carry both sanitary flows and storm water runoff to the treatment plant and the North Shore Channel during high runoff periods. But the original trunk sewers were of limited capacity.

The plan had been that as new homes and buildings were constructed in vacant areas, additions to the existing system would be made. That, however, did not happen.

Several major studies were undertaken with an eye toward rectifying the situation. The earlier ones came up with a recommendation that would have cost $160 million and increased Skokie’s bond debt 20 times, resulting in a 185 percent property tax increase.

Another study, conducted by Harza Engineering, proposed an acceptable alternative. It recommended that the village investigate the possibility of using inlet control technology to deal with the problem of basement flooding.

Inlet control technology involves restricting the rate at which rainwater flows off the streets into the sewers so as to prevent overload. The excess rainwater is temporarily stored in the streets.

A detailed engineering analysis is used to determine both the sewer flow and street ponding capacities. In areas where the level of street ponding could cause damage to nearby property, storm water storage facilities would be built or sewer improvements made.

In January 1982, the consulting engineering firm of Donohue and Associates conducted another study of the feasibility of inlet control for a specific portion of the village and determined that it could be implemented at a much lower cost than the earlier proposals.

With the results of that study, Mayor Albert Smith and the village Board of Trustees in 1982 authorized an inlet control flood relief program for the Howard Street Sewer District (most of the village area south of Oakton).

Tests were conducted, designs were detailed, and work began. In 1985 flow regulators, roadway berms, and underground storage facilities were installed. Construction of the necessary relief sewer system began in 1986, and the system was officially put into operation in April 1987.

A program for the remainder of the village has also been approved, involving a five-year schedule. Work is to begin with the installation of flow regulators and roadway berms in 1988. Underground and surface storm water storage facilities are to be constructed beginning in 1989. The relief sewer system is scheduled for construction in 1992.

And Skokie basements will be all the drier for it.

Orchard Mental Health Center

The Orchard Mental Health Center of Niles Township, which is often referred to simply by the acronym OMHC, has played an important role in the provision of community services over the past decade. An offspring of the Orchard School, which had been founded by Julia S. Molloy, for whom the Molloy Center in Morton Grove is named, OMHC was officially incorporated December 28, 1976.

The center, located today at 8600 Gross Point Road, was formed as a not-for-profit outpatient community agency with a goal to provide mental health services that are affordable for all citizens within the township.

According to its executive director, Dr. James J. Reisinger, “the center has grown notably in its capability to provide multiple forms of comprehensive outpatient services, including diagnosis and treatment from severe to everyday stress-management problems; family, group, and individual therapy programs; services for children and adolescents; 24-hour emergency services; substance abuse counseling; among many others.”

One of the more recent innovations at OMHC is the Transitional Living Program which, on a scattered-site apartment basis, provides time-limited housing services for mentally-ill adults in order to develop independent living skills and ease the integration of patients back into the community.

The center is funded chiefly by the Illinois Department of Mental Health, Illinois Department of Children & Family Services, Niles Township Administration, and the United Way of Skokie Valley.

The Threatened Nazi March

Early in 1977, American neo-Nazi Frank Collin wrote a letter to the Skokie Park District asking for permission to hold a rally in a village park. In almost any community imaginable, but especially in one with a large Jewish population, many of whom are survivors of Nazi death camps, the request was far from welcome. Park District officials responded carefully, ordering Collin to post a $350,000 insurance bond. Collin countered by announcing that he intended to demonstrate on May 1 against the Park District’s policies.

Mayor Albert Smith, Corporation Counsel Harvey Schwartz, and other village officials tried to remain low key, reluctantly taking the position that the First Amendment rights of the U.S. Constitution gave the neo-Nazis the right to demonstrate. But serious objections were raised in the community, and the threatened march became a major media issue throughout the nation.

Skokie’s Board of Trustees sought a court injunction against the demonstration. On April 28, Judge Joseph Wosik complied with the request to halt the May 1 demonstration, but Collin reacted by announcing that he would come to the village on April 30, the day before the date listed in the injunction.

On Saturday morning, April 30, Circuit Court Judge Harold Sullivan, a Skokie resident, issued an emergency injunction, ordering Collin and his associates to remain out of Skokie in uniform “until further notice of the court.” Even while the injunction was being handed down, hundreds of people bitterly opposed to the creed and presence of the Nazi party gathered on the Skokie Village Green. A confrontation was avoided when village police stopped Collin and his party at the Edens Expressway exit at Dempster Street and told them of the judicial ruling. The Nazis obeyed the ruling and left.

Subsequently the Skokie Board of Trustees passed three ordinances, all aimed at prohibiting future Nazi demonstrations in the village, and all promptly challenged by the American Civil Liberties Union. In a protracted legal battle that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, the ordinances were held unconstitutional.

Although the village of Skokie lost the legal battle, it won the war to keep Nazis from marching in uniform within the village limits. In 1978, Collin announced that he had really wanted to march in Chicago’s Marquette Park all along.

But the drama was not quite over. Because of the national interest the confrontation had garnered, a CBS network television producer, Robert Berger, created a made-for-television movie entitled Skokie about it. Many of the film’s scenes were shot on location in the village, including such sites as Village Hall, Niles East High School, and Temple Judea-Mizpah.

At the time Skokie was shown on television, neo-Nazi Frank Collin, however, was in no position to comfortably watch it. He was in prison for the crime of taking indecent liberties with a minor.

In Recent Years

In 1982, the Board of Trustees granted Group W Cable, Inc., a franchise to provide cable television service in Skokie. The village’s Cable Television Office, created to distribute information and investigate citizen complains, was established the same year. In 1984, the village created the Cable Television Advisory Board and the Skokie Cable TV Foundation, a not-for-profit corporation to promote local access programming. Today the cable television franchise is in the hands of Telecommunications, Inc.

Smoking, or perhaps not smoking, in Skokie received a good deal of publicity in the entire Cook County area in 1987 when the village decided to restrict it. The result was one of the toughest anti-smoking measure in the state of Illinois. Little public controversy, however, accompanied it in December of that year when Skokie passed its ordinance requiring non-smoking areas in all restaurants, schools, banks, and other buildings open to the public.

Reaction to the proposed neo-Nazi demonstration and the passage of a strong anti-smoking ordinance are prime examples of the village’s recent concern and confrontation with important social issues.

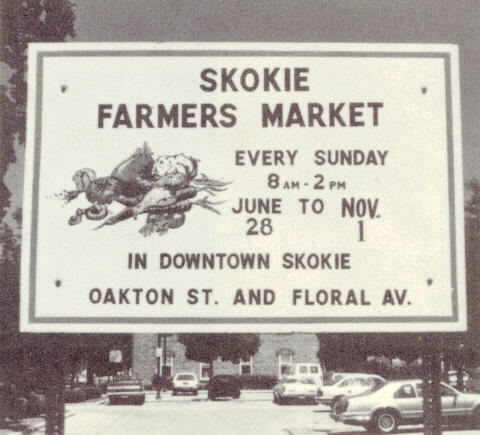

Skokie Farmers Market

Skokie Farmers Market

Fortman’s Nursery

Fortman’s Nursery

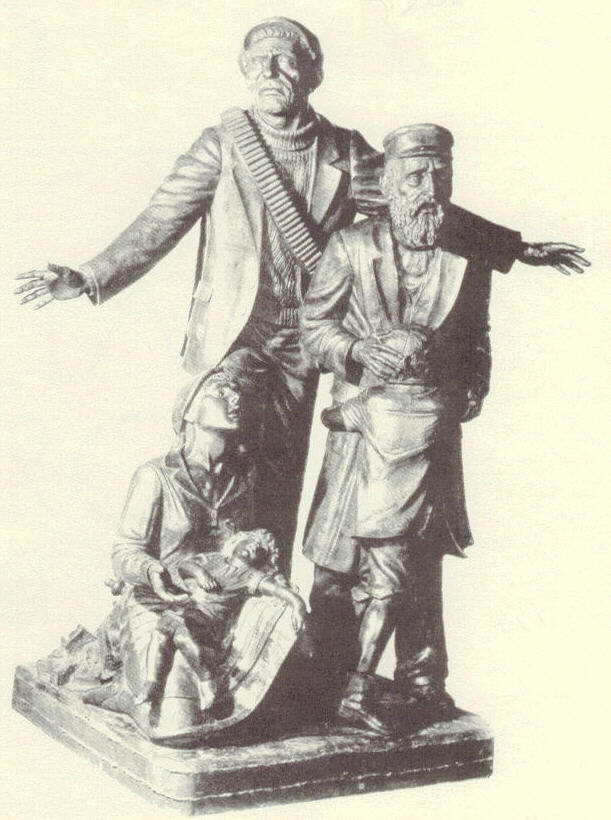

The Holocaust Memorial Monument

On May 31, 1987, a little more than 42 years after World War II came to an end, a monument to the approximately six million Jews and other victims of the Nazi Holocaust was unveiled in Skokie.

The site was most appropriate because, at the time, many Holocaust survivors resided within the village limits, more than those in the city of Chicago or any other suburb in the area. In addition, Skokie had faced the neo-Nazi march threat of 1977 and emerged victorious in their efforts to prevent it. Therefore, the idea was offered to erect a monument so that the horrendous Nazi crime of attempted genocide would not be forgotten. A committee was formed in the 1980s and work was subsequently started to bring the project to fruition.

The committee approached village officials seeking a proper public location for the monument. Mayor Albert J. Smith and the Board of Trustees agreed that village property could be used, the site selected to be on the grounds between the Skokie Public Library and Village Hall.

A sculpture design by Chicago artist Bert Gast was then approved. The resulting statue, which symbolizes the attempted destruction of European Jewry, contains the depictions of a freedom fighter, a youth clinging to his grandfather, and an anguished mother cradling her dead child. The three generations of victims are set upon a symbolic detritus of bricks, torn prayer books, a menorah, and other items.

The inscriptions on the statue were carefully selected upon advice from various Rabbis and other experts. It was agreed that the statue would bear six names of extermination camps, one for each million victims, and a saying from the book of Lamentations, both in its original Hebrew and in English translation.

Funds were raised over a two-year period from private sources, and a ground-breaking ceremony was held April 6, 1986. A little more than a year later, the memorial was formally unveiled; its purpose, in the words of the committee that brought it to reality, “to remain in perpetuity as a reminder of what hate can do to mankind if decent people are not vigilant to forestall such a calamity in the future.”