4 Niles Center

NO RESIDENT failed to note the well-publicized event when the village changed its name to Skokie in 1940. But a much earlier name change was only vaguely noticed. The official name of the village when it was incorporated in 1888 was Niles Centre. But three years later, the October 1, 1891 edition of the Chicago telephone directory changed the spelling to the Americanized Niles Center. Over a period of more than two decades, villagers gradually adopted the new spelling. Still, for years, stores, billboards and signs displayed a mixture of the two spellings. The Village Board, in fact, was one of the last organizations to continue using the original spelling. Clerks Frank Wagner, Peter Blameuser, III, John Paroubek, Henry Heinz and George Busscher, Jr., all prepared their documents using the original spelling. The practice ended without fanfare, however, by the time Anthony Paroubek became clerk in 1910.

A Little Capital of Silent Films

Beginning around 1905 before most of the large movie studios moved west to Hollywood, the heart of Niles Centre was the location for the filming of dozens of silent movies produced by the old Essanay Film Manufacturing Company. Soon after the turn of the century, Essanay began producing silent films at its studio at 1315 Argyle in Chicago. Among the stars who began their careers there were Gloria Swanson, Wallace Beery, Ben Turpin, Pauline Frederick, Edward Arnold, the Keystone Cops and the Our Gang kids. Wallace Beery and Gloria Swanson were married in the same studio.

Because the downtown area of Niles Centre resembled a western town, Essanay executives decided to use it as a location for outdoor sequences in many of its popular cowboy and Indian movies. During the early 1900s, wagonloads of actors and actresses traveled daily to Niles Center, where elaborate scenes, including gunfights and Indian attacks, were filmed.

“I can remember that old camera being cranked away while furious gun battles were held right at Oakton and Lincoln,” area resident A.J. Linderman recalled decades later. “We kids got so used to seeing ambushes and men tied to trees with arrows going right through them,” Linderman continued, “that we considered it a very normal part of the scenery.”

Around 1915, soon after the first electric lines came to the village, the Niles Center Theater was built and began showing some of the very movies that had been filmed in town. “I remember that admission was a nickel for kids and 10 cents for adults,” Linderman said. “I also recall the fun we had watching them make the movie, The Clutching Hand, starring Pauline Frederick, and then seeing it in serial form all winter long at the movie house.” Postmaster Samuel Meyer provided the music to go along with the silent movies by pumping an old player piano.

As glorious as they were, Niles Center’s years as a movie capital were short-lived. Not long after 1915, Essanay owners George K. Spoor and “Broncho Billy” Anderson, a well-known silent movie cowboy, finished moving their operation to Hollywood, where, among other ventures, they produced movies by Charlie Chaplin. For many, the excitement of those years far outlasted actual events. “What a thrill we got when we sat in our seats,” Linderman recalled of his youth, “and realized that people all over the country were seeing movies made in our home town.”

Making Movies

Before movie-making was even contemplated by the glitter-gulch of Hollywood, Niles Centre was a favorite location for filming westerns of the silent screen. The following newspaper account was unearthed by Skokie resident Richard J. Witry for his book, The Luxembourg Brotherhood of America, 1887-1987. The account of this hair-raising albeit ill-fated movie was provided by Tony Seul, who, in 1912, owned a saloon and restaurant, according to Witry, “located in the building owned by Peter Blameuser at the northwest corner of Lincoln and Oakton, presently the site of the Desiree Restaurant.”

“Tony remembers one day in 1912 when the movie men came into his place, had a round of drinks and gave him some tickets for the picture they were about to film. At the start of this melodrama, the actors staged a fearless bank robbery in the Niles Center State Bank and then ran across the street where their horses were stamping against the ties which held them to their hitching posts. In a blaze of shots and frenzy, they were off. One of the horses stumbled and fell upon his unfortunate rider who was fatally injured.

“After the wounded man had been driven away to St. Francis Hospital the producers came back into Tony’s and asked for the movie tickets, because they explained, ‘this won’t even be a picture’.”

Stability and the Railroad

Historical accounts of the arrival of the village’s first railroad differ, with several citing the years 1910 to 1915. But revised records of the Northwestern Railroad, and some local newspaper accounts made in later years, indicate that two sets of tracks were constructed as a branch line through the village in 1903. With some degree of certainty, it seems safe to say that Niles Centre residents could travel by train to Chicago for the first time in 1903 or 1904 merely by walking to the Northwestern station at Oakton Street just west of Cicero, instead of traveling the much longer distance to Morton Grove.

“Tony remembers one day in 1912 when the movie men came into his place, had a round of drinks and gave him some tickets for the picture they were about to film. At the start of this melodrama, the actors staged a fearless bank robbery in the Niles Center State Bank and then ran across the street where their horses were stamping against the ties which held them to their hitching posts. In a blaze of shots and frenzy, they were off. One of the horses stumbled and fell upon his unfortunate rider who was fatally injured.

“After the wounded man had been driven away to St. Francis Hospital the producers came back into Tony’s and asked for the movie tickets, because they explained, ‘this won’t even be a picture.”

In the earliest days, service consisted of southbound trains to Chicago at 7:30 and 10 a.m., and northbound trains from the city at 3 and 6 p.m. Sometime later, service was increased to three trains in each direction. Apparently there was some initial concern that the new train system would bring undesirable elements to the village. In later years, George E. Blameuser recalled how “a marshal met each train as it came in and if a stranger got off he had to have business in Niles Center or he’d go into the calaboose.” The village jail was located in the old firehouse on Floral Avenue.

The first village gatekeeper for early Northwestern trains was Ferdinand Baumann. He raised and lowered a pump-operated gate where the tracks crossed Niles Center Road. He also built a tiny park about 50 feet square near his gate complete with walks and a miniature zoo.

Despite the allure of farmer’s market days, the movie ventures of Essanay Films and the arrival of the Northwestern Railroad, life in Niles Centre remained relatively relaxed, especially compared to the teeming city of Chicago, whose population by 1900 had reached 1,698,575. Most of the approximately 1,698,000 fewer residents of Niles Centre apparently wanted to keep it that way. In 1906, an ordinance was passed barring children under the age of 15 from the streets after 8 p.m. Four years later, the newly elected Village Board President George Klehm closed the all-night dram shops.

A sure sign of stability and growth was the opening of the village’s first bank in 1907. Operated in the Blameuser Building, the Niles Center State Bank was founded by Peter M. Hoffman, George H. Klehm, John W. Brown, William Galitz and A.B. Williams. Peter Hoffman, more than anyone else, was the guiding force behind the bank’s organization, but his duties as Cook County Coroner (he also served as a county commissioner in earlier years) left only limited time to devote to the bank after it was organized.

John W. Brown was the bank’s first president and, for a number of years, William Galitz was the only employee. Galitz later became president as well.

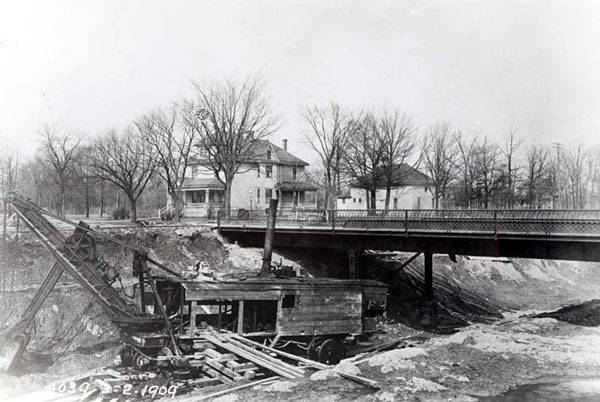

In 1910, when the population of the village was 568, work on the North Shore Channel of the Metropolitan Sanitary District of Greater Chicago was completed. The eight-mile canal ran from Lake Michigan at Wilmette to the North Branch of the Chicago River at Fullerton. There was, unfortunately, a two-mile-wide strip of unincorporated territory between the eastern boundary of the village and the canal. It was almost a decade before the village sewers were completed and the rights obtained to connect them to the sanitary canal.

During the year 1910, George H. Klehm also organized the village’s first baseball team. Surnames of the players on the 10-man roster included Baumhardt, Brown, Klehm, Remke, Rose and Schmidt.

On August 29 of that same year, the Chicago Telephone Company began operating an exchange in Niles Center, providing crank-type service to the area and free calls to neighboring Niles and Morton Grove.

The Bachelor Maidens, a group of young women who formed a social club and sponsored a dance each year queue up here somewhere around 1900. Leading what looks like a version of the Bunny Hop is Alma Klehm.

The Bachelor Maidens, a group of young women who formed a social club and sponsored a dance each year queue up here somewhere around 1900. Leading what looks like a version of the Bunny Hop is Alma Klehm.

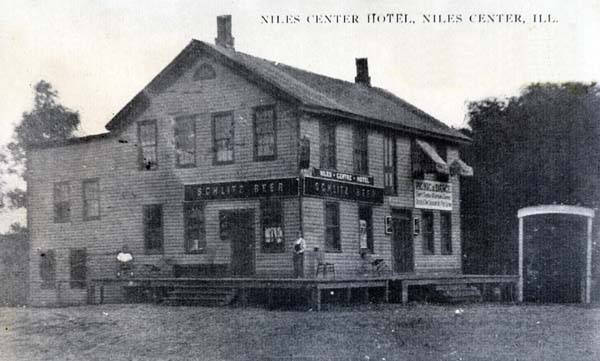

The Niles Centre Hotel, replete with saloon, located on today’s southeast corner of Oakton and Lincoln, was the site of this pre-Prohibition picnic and dance.

The Niles Centre Hotel, replete with saloon, located on today’s southeast corner of Oakton and Lincoln, was the site of this pre-Prohibition picnic and dance.

The Big Fire of 1910

It began on what village residents remembered as a “windy day,” but the exact date of the fire that destroyed much of downtown Niles Center has never been established, even though it was known to be a market day.

There were no village newspapers in Niles Center in 1910, and reports in other area newspapers were limited. For many years, the fire was believed to have occurred in October, but recent research has uncovered a reference to it in the Evanston Press of September 10, 1910.

The exact cause of the fire has never been determined either, although it is known that it began in a barn used to make wine behind the saloon of Jacob Melzer. His establishment was located on the west side of Lincoln Avenue just north of Tony Seul’s business at the corner of Lincoln and Oakton. According to one eye-witness report, “great shafts of fire started simultaneously everywhere.”

The fire began in the midst of a prolonged dry spell, and the wind undoubtedly promoted its rapid spread. People along the west side of Lincoln Avenue worked desperately to save their buildings, climbing to the rooftops and wetting them down with mops and brooms dipped in buckets of water which were pulled up by ropes. The volunteer fire department had a hand pumper to draw water out of cisterns, but with no central water system in the village, the supply was woefully inadequate. All able-bodied men in the area joined the volunteers to form bucket brigades which tried to douse the fast-growing fire. With the help of George Blameuser, Mrs. Bertha Rosche pieced together more of the story for her manuscript, Setting Down the Record…

“Calls for help were sent to Morton Grove and Niles,” she wrote, “and they contributed their volunteer fire departments, though they, too, were largely dependent on bucket-passing.

“Then the call for help reached Evanston and Chicago. They responded with an engine and company apiece. They laid their hoses to the lagoon belonging to the Peter Blameuser family, west of their large old home . . . Without the little body of water the town doubtless would have been doomed.”

Some accounts of the fire’s duration differ, but its aftermath was all too clear. Much of the block on the west side of Lincoln, from the Blameuser Building (which was spared, probably because of the direction of the wind) northward about four lots had been destroyed. Since there were only a few buildings on the east side of the street, the fire essentially consumed the heart of Niles Center’s business district.

The fire itself was not the only problem. It occurred on a market day, a time when hundreds of outsiders had crowded into the streets of the little village. As the fire spread along Lincoln, residents began carrying their belongings out onto the street, hoping to save at least some from the conflagration. Instead, they made their possessions all the more accessible to thieves, who began looting as soon as goods were carried into the open. Mayor George H. Klehm worked quickly to deputize an emergency force of police officers to battle against thievery.

It was the Blameuser family lagoon, along with the efforts of many fire fighters, that is generally credited with saving the town from complete destruction. The little pond that eventually provided water to douse the flames had been created when Blameuser dug clay out of the ground behind his house on Oakton east of Lincoln for the purpose of selling it. Later, the hole was filled with water and used for ice skating and as a source of ice in the winter. George E. Blameuser recalled that his family “used to cut 2,500 tons of ice a year from the lagoon.” But the lagoon had never been put to better use than in September 1910, and many area residents expressed their gratitude to the Blameuser family for years.

The tragic fire had two positive side effects, however. Just as Chicago’s residents had done following that city’s historic fire of 1871, which also began in a barn and occurred during a drought, the residents of Niles Center began rebuilding almost immediately, constructing stores and other buildings more substantial than those which had been destroyed in the fire. The disaster also pointed out the village’s very obvious need for a central water supply. The project to fill that need got underway shortly thereafter and was completed within a few years.

An Interesting Decade

The decade following Niles Center’s great fire was a time of lively and decidedly mixed events. In 1911, the year that neighboring Tessville, later renamed Lincolnwood, was incorporated, the Niles Center Hotel, built by Henry Harms and at one time rented by Fritz Rose, was completely destroyed in another spectacular fire.

In that same year, a farmer named Fred Guelzow, a member of the Cook County Truck Gardeners and Farmers Association, an organization created by George H. Klehm and others in 1902 and incorporated the following year, was murdered, his body found on Lincoln Avenue.

At about the same time, and on far less disastrous notes, the present St. Paul’s Evangelical Lutheran Church building was constructed and the Northern Illinois Gas Company built a large manufacturing and storage facility at McCormick and Oakton. The five million cubic foot cylindrical storage tank remained a familiar landmark in the area until it was dismantled in 1963.

Two years later, in 1913, law enforcement officials began rounding up horse thieves in Cook County, alleged by some to have more rustlers than the combined areas of Texas, Wyoming and the Dakotas. Some of the thieves, it is believed, hid out in the huge Skokie Marsh, which spread northward from Niles Center.

Of more lasting importance in 1913 was the construction of the first mile of paved concrete road in Cook County outside of Chicago, on land annexed to Niles Center 11 years later. The road was a stretch of present-day Church Street, from Niles Center Road eastward to Keeler.

Instrumental in acquiring $10,000 from the county to help finance the project was George Landeck, who was born within the boundaries of the village in 1867. Prominent in local and county affairs, he had served as highway commissioner for 18 years and was a president of the Niles Township Improvement Club and the village volunteer fire company.

In 1961, workers widening and resurfacing Church Street found a plaque at the intersection of Church and Kolmar commemorating the historic 1913 project.

Although Niles Center market days would continue on a smaller scale for at least two more decades, the tradition (since 1880) began to decline around 1914, the same year the first battles of World War I broke out in Europe. As a result of the war, the DuPont Powder Company, in 1915, began assembling lumber and other materials to construct what was called “the world’s largest powder factory,” actually a dynamite and TNT plant a few blocks from the intersection of Lincoln and Oakton.

Alarmed by the prospect of huge quantities of explosive gunpowder being manufactured near the heart of downtown Niles Center, a group of about 500 people (roughly the entire adult population of Niles Center) petitioned the Village Board to do something about the looming danger to their community. Mayor George H. Klehm telephoned A. Poehlmann, the mayor of Morton Grove, and Frank Meier, mayor of Tessville, to galvanize local opposition. At a meeting between company representatives and the three mayors, an agreement was reached in which the company promised to move out of Niles Township in return for payment for lumber it had already acquired. A check was advanced at the same meeting, and the company abandoned the site the next day.

Far greater local approval was given to the Chicago, Fox Lake and Northern Interurban Railroad Company which, in 1916, was granted a franchise by the Village Board to build an east-west street car railroad along Oakton Street. By 1918, however, the year service was supposed to begin, few additional steps had been taken to build the line, and, in fact, it was never built. At least two other similar ventures also failed.

The era from 1910 to 1920 was certainly less tumultuous for Niles Center than for the United States and the rest of the world at war. The village had continued to grow, but slowly, reaching a population of 763 by the end of the decade. There had been significant amounts of progress, however. Municipal sewers, long blocked from the sanitary canal beyond the eastern border of the town, were finally hooked up. This marked the end of nearly a decade-long battle to build a sewage system emptying into the canal, a vast improvement over the septic tank once recommended by Sanitary District employees. During the same era, electric lights were installed along a number of village streets and gas lines were run to commercial and residential properties. The groundwork for growth had been laid.

The Dinkey Line

In the early 1900s, many wealthy Chicagoans traveled to the private Glen View Golf Club in the village of Golf, and the journey was considered to be quite a trip. Most took the old St. Paul Railroad, now known as the Milwaukee Road, from Union Station in Chicago to the depot at Golf. From there they traveled to the club by carriage or horse drawn bus.

On September 29, 1906, George P. Merrick and other members of the Glen View Golf Club incorporated the North Shore & Western Railway, for the purpose of constructing a tiny rail line from north Evanston to the golf club grounds, following Harrison Street a bit north of Sharp Corner. On July 24, 1907, the line was completed to the North Branch of the Chicago River. A month later, a trestle was finished to cross the river, allowing the line to run directly to the Glen View clubhouse. The total length of the NS & W line was about 3 3/4 miles. The fare for riding its full length was 20 cents.

The NS & W Railway actually resembled a trolley car line more than a railroad. On July 11, 1907, a single car (used) was purchased for $1,500, equipped with an electric motor and a pole that rose to an electrified wire. A second car was purchased the following year, but it was turned into a snowplow and disposed of a few years later. The remaining car of the NS & W Railway became known as the “Dinkey.”

The NS & W Railway had only two employees, the Dinkey’s engineer and a conductor. The officers of the corporation served without pay, and ridership was low. But the Dinkey was given a boost in 1913 when the Westmoreland Golf Club was opened along its rail line. The NS & W’s two employees, it was noted, however, sometimes had to put up with the pranks of golf caddies traveling to work. The caddies were said to enjoy crowding into one end of the car and rocking it until they knocked the electric pole off the wire.

Not all the merriment associated with the Dinkey was of the rowdy kind. The Glen View Golf Club had frequent parties, which usually ended around 11:30 on weeknights. The last eastbound run was packed to standing-room capacity and on occasion featured barbershop quartets singing on the rear platform.

The opening of Memorial Park Cemetery in 1917 in an area along the rail line brought many additional riders to the Dinkey. These new fares were instrumental in keeping the Dinkey running into the 1920s.

Beginning in 1921, officers of the Evanston Railroad took over the NS & W’s management from George Merrick. One of them, C.F. Speed, helped create a public golf course on Harms Road, providing additional fares for the Dinkey.

The Dinkey was seldom more crowded than on Sundays when thirsty Chicagoans, parched by a city blue law prohibiting the sale of alcoholic beverages on that day, traveled on the little line to a “blind pig,” or speakeasy, which was operated in Harms Woods.

A five-year contract signed between the railroad and Glen View Golf Club expired in 1926. By this time, automobile travel was becoming routine, and the club no longer felt the need to subsidize the rail line. When C.F. Speed suggested extending the tracks to downtown Glenview, the club instead tore up the track crossing its land.

More than 38,000 passengers rode the Dinkey in 1926, but ridership fell off soon thereafter. Only 4,512 tickets were sold during all of 1932. Following a number of service cutbacks, the line was abandoned on December 18, 1935. Few traces of it remain.

The Chicago Rapids Transit Company

By the early 1920s, the populations of Chicago and the suburban towns along Lake Michigan had grown substantially. In 1923, Chicago’s expanding population required, theoretically, the construction of ten new blocks of homes and apartment houses annually, and towns such as Evanston and Wilmette were unable to meet the demand for more home-sites. The Skokie Valley area offered a tempting site for the overflowing urban population.

Even before 1920, real estate speculator Samuel Insull realized that Niles Center was in the right place to experience a real estate boom. He organized a group of investors to exploit it.

Insull controlled the Public Service Company of Northern Illinois, which had installed high-tension electrical lines with a wide right-of-way through the Skokie Valley and extending northward. From the beginning, it was planned to use the route for multiple tracks.

The largely undeveloped land in the Skokie Valley and to the northwest toward Libertyville was ideal for the construction of a rapid transit system for several reasons. First was the open, relatively flat land with rights-of-way already obtained. But of even more importance were the two rail lines built by the North Shore Line to the east and the west of Niles Center. To the east was the North Shore Line at Evanston, which connected that suburb with Chicago’s elevated system, operated by the Chicago Rapid Transit Company. To the west was the North Shore’s suburban route from Chicago through Libertyville.

Anticipating rapid development in the Skokie Valley and northward, Insull and his associates decided to construct a line connecting the two other railroads, one that would pass through Niles Center. The Chicago North Shore & Northern Railroad was organized in 1924 as a subsidiary of the North Shore. Work on the first leg of the extension, from the elevated tracks at Howard Street to Niles Center, was begun April 24, 1924.

The project necessitated the construction of seven steel and concrete trestles, the largest of which had a 1,000-foot span crossing a drainage canal and several other railroads. A tunnel also had to be excavated under the Chicago & Northwestern Railroad main line. A total of eight stations, built of brick, reinforced concrete and marble were erected along the line.

Despite the size of the project, work was completed by early 1925. The Chicago Rapid Transit Company began service on the still unfinished line on February 1. With a great deal of fanfare, it was officially dedicated during a ceremony at the Dempster Street station (today the terminus of the Skokie Swift) on March 28. As many as 1,500 workers then labored from June 1925 until June of the following year to complete the remaining 18 miles of track to Libertyville.

In his book, North Shore: America’s Fastest Interurban, author William D. Middleton quoted some of the new railroad president’s words at the official dedication ceremony June 5, 1926. “The Skokie Valley Route of the North Shore Line represents an investment of $10,000,000 in the future of the comparatively undeveloped North Shore region lying to the west of the territory now served by our Shore Line Route. We have made this big investment secure in our confidence that this region is destined to become one of Chicago’s most beautiful and desirable residential districts. We have every reason to believe that our confidence is not misplaced. “

A moustache cup used by an early resident, from the Skokie Historical Society collection

A moustache cup used by an early resident, from the Skokie Historical Society collection

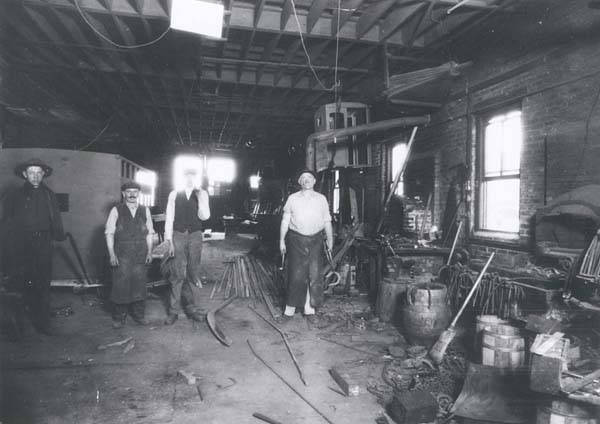

A view inside Fred Schoening’s blacksmith shop about 1926. The building itself still stands at 7880 Lincoln Avenue.

A view inside Fred Schoening’s blacksmith shop about 1926. The building itself still stands at 7880 Lincoln Avenue.

Real Estate Boom

Months before the first trains from Chicago ran on the elevated tracks, Samuel Meyer, owner of a general store on Lincoln Avenue and the oldest lifetime resident of the village, reported: “The ‘L’ extension has already changed everything . . . I expect (my) store with its 200 feet of frontage on Lincoln Avenue is worth $50,000 or $60,000 today. When it gets up to $1,000 a foot I think I’ll sell it. But I’ll never leave Niles Center…

“There isn’t any trade any more in the store,” Meyer continued, “but the increase in the value of the ground under it more than makes up for that. There is no trade because the subdividers bought up all the farms and our trade was with the farmers.”

Meyer was not the only person to note that the value of Niles Center land was heading upwards. The pages of Chicago business periodicals were filled with get-rich-quick stories about entrepreneurs speculating on land near the new elevated tracks in Niles Center. “An operator has just closed the purchase of seventy acres half a mile from the right-of-way for $210,000, or $3,000 an acre,” one paper reported. “One operator bought ten acres on Main Street near the Chicago, North Shore and Northwestern three months ago for $25,000; he sold one plot for $5,000 and has sold the rest for $45,000.”

Niles Center State Bank President Willard C. Galitz told a story about a corner lot, 75 x 125 feet, at the intersection of Lincoln and Main. “That lot sold for $3,200 two and a half years ago,” he said. “It was resold eighteen months ago for just about $10,000. Then six months later it was sold again for $20,000, a bit more than double. Now it’s on sale for $45,000.”

Throughout most of the 1920s, tales like this multiplied all over Niles Center and in the areas around it. With real estate values skyrocketing, many towns in northern Cook County cast covetous eyes at the unincorporated regions around them.

Niles Center Expands

In 1922, despite the early years of the Niles Center real estate boom then underway, the boundaries of the village had remained unchanged for nearly 34 years. During the next four years, however, the incorporated area of the village would be increased to more than 10 times its original size. This expansion was accomplished through a number of annexations, a legal process formalized in an Illinois state law of July 1, 1872.

The law basically provided for the annexation of unincorporated land by a petition signed by a majority of the land owners and voters of the land in question, followed by a formal referendum.

A huge area of land was annexed to Niles Center on January 28, 1924. It was bounded on the south by Howard Street, on the east by the eastern boundary of Niles Township (about 100 yards east of the sanitary canal, often cited erroneously as the village’s new eastern boundary), on the north by Golf Road, and to the west by Gross Point Road, Iserman Road and the eastern boundary of the original Niles Center limits. This first annexation remains the largest in Skokie’s history.

Two more sizable parcels of land were added in another annexation on January 29, 1925. One was a roughly rectangular parcel extending due northward from the original northern boundaries of the village and the other was a very irregular area to the south, bounded, at various places, by Touhy, Jarvis and Pratt Avenues.

Land extending a substantial portion of the village’s northern boundary to Central Avenue was annexed on January 8, 1926. Smaller annexations were made in 1928 and 1930, by which time the village assumed the general shape it has today. There were, however, a number of minor changes over the years, involving annexations, disannexations and even reannexations. A typewritten manuscript detailing all of them, entitled “The Geographical Growth of Skokie, Illinois,” by Joseph C. Beaver, is available either at the Skokie Public Library or from the Skokie Historical Society.

Local doughboy saluting Ollie Dotzhauer.

Local doughboy saluting Ollie Dotzhauer.

A patriotic gathering at the southeast corner of Lincoln and Oakton in 1918 held under the auspices of the village’s Women’s Patriotic Service League

A patriotic gathering at the southeast corner of Lincoln and Oakton in 1918 held under the auspices of the village’s Women’s Patriotic Service League

A steam shovel dredges out the channel for the MSD Sanitary Canal.

A steam shovel dredges out the channel for the MSD Sanitary Canal.

Niles Center area for sale

Niles Center area for sale

The Boom Goes On

Since 1919, the Volstead Act has limited the amount of alcohol in beverages sold in America to a sober one-half of one percent of total volume. It must have strained the credulity of local police to believe that alcohol remained under that legal limit in the many speakeasies that flourished in the Niles Center area during the Prohibition Era. Americans by the millions danced the Charleston, listened to jazz, and sipped bootlegged booze and many members of the fast-growing population of Niles Center obviously enjoyed the spirit and spirits of the times along with them.

Besides being the age of flappers and bootleggers, the Roaring 20s carried with it a minor population explosion in Niles Center. In some individual years during the decade, the population of the village increased more than it had during its first four decades. The population of Niles Center in 1920 was 763. Ten years later, it had grown to 5,007.

Speakeasies were not the only form of free enterprise that sprang up to serve the fast-growing community. The village’s first two newspapers, the Niles Center Press and The News, began publishing weekly editions in 1924 and 1925, respectively.

The Niles Center Businessman’s Club, which eventually became the Skokie Chamber of Commerce, was formed on April 17, 1925. It was needed as a result of the growing number of businesses in the village. The Woman’s Club of Niles Center, now the Woman’s Club of Skokie, was organized the following year. The first large office building in the village was constructed the following year. The Bronx Building, built for $170,000 at the corner of Bronx and Dempster, was considered for years to be one of the most magnificent buildings in all of Chicago’s suburbs.

On December 8, 1928, the National Bank of Niles Center, the first nationally chartered bank in the township, opened its doors with Ferdinand Baumann as president. That same year, 162 new houses were built with a combined value of more than $2 million. As they had in earlier years during the decade, real estate speculators continued to buy land, subdivide it and build streets complete with curbs and sidewalks.

The soaring growth of the town brought unprecedented demand for municipal services. Village officials issued Niles Center’s first building permit in 1925 for a gas station at the intersection of Niles Center Road and Church Street. Hundreds more were issued during the next four years. Mayor John E. Brown and the Village Board issued a continuing flow of contracts for water and storm and sewage lines (some with diameters as large as 84 inches) as well as street improvements needed for a town that then was anticipated to reach 200,000 inhabitants in the relatively near future. In July 1926 alone, a half million dollars in contracts were approved by the village for water, lights and sewage disposal.

Since the village was incorporated in 1888, most municipal business was conducted at the old firehouse on Floral Avenue but, by the early 1920s, the need for larger quarters was obvious. On the site of Henry Harms’ earliest homestead in the area, the Niles Center Municipal Building, today’s Skokie Village Hall, was constructed in 1927. The following year saw the creation of the Park District of Niles Center and the dedication of the Northside Sewage Treatment Plant, largest of its type in the world, at the intersection of McCormick and Howard.

New schools in the village reflected the expanding population. By the end of 1926, Niles Center had six public schools, including the old Niles Center and Fairview schools, the East Prairie and Sharp Corner buildings, and the brand new College Hill and Bronx schools. Despite the proliferation of public schools, the school at St. Peter’s Catholic Church maintained the largest enrollment, numbering 243 in 1928.

As the end of the decade neared, there seemed little to stand in the way of the burgeoning growth of the town that, since 1925, had adopted the slogan “Niles Center—We Do.”

The World’s Largest Village

In the 25 months from December 1923 to January 1926, the incorporated area of Niles Center increased from less than one square mile to more than 10 square miles. In that short time, Niles Center earned the distinction of becoming the largest area in the United States under the village form of government, establishing Skokie’s later claim as “The World’s Largest Village.” The reason for the phenomenal growth was the arrival of the elevated tracks from Chicago, which precipitated the area’s sudden real estate boom.

The Niles Center Crash

The effects of the stock market crash of 1929 and the international depression that followed it were felt in Niles Center for decades, even after it had been renamed Skokie in 1940. Virtually all construction in the village stopped in the earliest months of the Depression. Seven years later, when the nation and the village were still suffering from the economic collapse, Mrs. Bertha Rosche came to Niles Center to begin directing the village library.

“Even a stranger could read in the very pavements the story of boom and bust,” she wrote. “There lay the streets, crisscrossing the wide-open prairie through neat rectangles — with grass growing up through the cracked asphalt! The curbs and sewers and walks were in, but the streets were silent. Over the empty prairie, with views of a mile in any direction, here and there rose a lone apartment house. It was customary to walk in the streets since there was no traffic, for the sidewalks were heaved by the frost and the broken squares of cement tilted crazily…

“Tessville farmers and Morton Grove folk and those at Niles must have watched pea-green with envy while their neighboring villagers sold their farms for sums that occasionally reached six figures. But, if they missed the boom, they were spared the collapse. Twenty-five years more and another world war were to pass before they had their turn, and then it would be in real estate development that had a firm foundation and stability — not the mirage of speculation.”

The depression in the construction trades, of course, was mirrored in most areas of the local economy. The Niles Center National Bank failed. (The Niles Center State Bank survived, however, and later became the First National Bank of Skokie.) By June 1930, more than 100 people in Niles Center were unemployed. By November, Mayor Brown asked the growing number of unemployed townspeople to register with the village as part of a program to provide work for everyone. “Registration of Niles Center’s unemployed is continuing at the village clerk’s office,” the Greater Niles Center News reported in its December 5 edition, “and… more than 100 job applications have already been received… Of that number, more than 30 have already been given work.”

Many of the jobless were employed by the Park District of Niles Center, created on February 3, 1928. The crews were put to work clearing land, purchased in 1929, that eventually became Oakton and Emily Parks. Most of the men worked on alternating shifts, so that more could be employed.

Despite the best efforts of the village government, it was impossible to halt the rising tide of economic distress and widespread unemployment. On October 30, 1931, Mayor Brown of Niles Center and Mayor Herbert Dug of Morton Grove issued a joint proclamation calling for winter relief for the families of all area men left unemployed.

The list of bad news from the early 1930s seems almost endless. George H. Klehm, one of the village’s most prominent civic leaders, died of a heart attack in May 1932. By the following year, America’s “Largest Village” saw only seven houses built within its borders, 155 fewer than in 1928, shocking testimony to the power of the national and local financial collapse.

The effect of the Depression on area businesses is also illustrated by the Chamber of Commerce’s inability to collect its $25 annual membership fees in 1933. The dues were lowered to $5 a year.

The village’s National Bank of Niles Center was reopened in March 1933 but in April was robbed of about $5,000 by three armed bandits. Returning from a coffee break, a Morton Grove man named Harry Mueller, who worked in the bank as a cashier, was killed by one of the criminals. All three robbers were eventually caught and imprisoned. The bank failed the following year, and a receiver was appointed to liquidate its assets.

Just two years after newly elected Mayor George Blameuser formally organized the Niles Center Police Department, its two highest ranking officials were charged by the State’s Attorney’s office with “shaking down” motorists involved in alleged traffic offenses.

On November 28 of that infamous year of 1934, the body of notorious gangster “Baby Face” Nelson was found just north of St. Paul’s Cemetery in Niles Center.

For more than three decades, the village had been served by the two parallel lines of the Northwestern Railroad’s branch line through Niles Center. “But somewhere around 1935,” a 1963 edition of The Life newspaper recollected, “a form was incorrectly prepared and approved in the railroad’s office.

“Before anyone realized what was happening,” the story continued, “a work crew came out to Niles Center and ripped up one of the two tracks. When the error was discovered, it was too late to do anything about it.” Until that time, the line had six trains a day providing service to the village. After the error, service had to be reduced to three, two southbound trains in the morning and only one in the evening.

Although the story of the “clerical error” has often been retold, many area residents and historians doubt its authenticity, suggesting instead that the widespread hard times and business decline were more likely the cause.

Like most of the rest of America, Niles Center, however, fully recovered from the Depression during the years of the war economy of the 1940s. Those who lived through it, and even their children, had been severely affected by the difficult times. But, perhaps not surprisingly, some of the most lasting institutions in the village had their roots implanted in the era of America’s Great Depression.

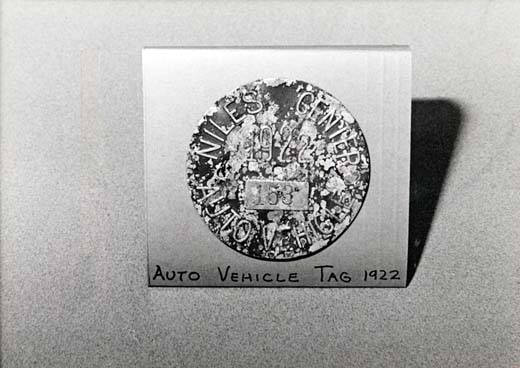

Auto Vehicle Tag

Auto Vehicle Tag

Village Hall

Skokies Village Hall, located at 5127 Oakton, was built in 1927, when the village was still named Niles Center. It was erected on land purchased for $9,000 from an heir of Henry Harms. Designed along the lines of Philadelphias historic Independence Hall, the most notable features of the edifice include four large wooden columns and a gold cupola, a fitting crown for the village that experienced its first great land boom during the Roaring 20s.

Bronze tablets on both sides of the main entrance provide the names of builders, town government and civic leaders and other historic information. The building was remodeled extensively during the 1950s, and the southern section and the garden entry were added in 1980.

Depression Era Progress

Many of the improvements in and around Niles Center during the 1930’s were made by federal and local governments anxious to create work for restless and desperate armies of unemployed people. One of the earliest benefits of depression-era politics was home delivery began during the early months of the Depression.

“House to house delivery of mail will start April 1” The News announced in it’s front-page story of January 31, 1930. “Two men, one on foot and one with an automobile or truck, will be Niles Center’s first postmen. One delivery each day, six days a weeks is the present schedule, Postmaster (Herman) Meyer said…Niles Center, will get it’s mail from the Evanston office, beginning tomorrow. In years past the mail has been brought to Niles Center from Morton Grove by Postmaster Charles Kindt, who is to retire after today,” the article went on to report.

House-to-house mail delivery was not the only benefit to area residents of the federal government’s efforts to fight unemployment caused by the Depression. In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt included the creation of the Skokie lagoons in the reforestation projects. “Drainage of the Skokie marsh region, which will do much remedy flood and health problems in this section, is expected to start within the next few days…” the Niles Center Press reported on June 23, 1933. “Tools, trucks and necessary supplies will be furnished by the government when the large crops of laborers and supervisors are set to work. It is estimated that nearly 1,000 men will be encamped near here when the project gets underway.”

The familiar Skokie lagoons are located well north of the town that now bears the same name, just as much of the Skokie Marsh was well always north of Niles Center. The lagoons can be found just east of the Edens Expressway, extending roughly from Willow Road, northward to the Lake County line. Like the earlier efforts of Henry Harms and the later effects of the Deep Tunnel Project, the lagoons did much to retrieve the land from swamps and spring floods and make it livable year-round for area residents.

Various branches of county and local administrations were, like the federal government, particularly active during the Depression years. Lincoln Avenue, difficult to maintain since its earliest days, became an Illinois state highway in 1932. The Niles Center Board of Health was established on February 17, 1931 but its first full-time employee, Helen Lies, R.N. was not appointed until nearly five years later. The Park District began acquiring land for numerous parks during this period, including land which later became Central Park in 1931, Lorel Park in 1937 and Lee-Wright Park in 1939.

Perhaps the most important contribution of both local and federal governments was the creation of the township’s first high school. On September 8, 1931, six teachers began providing classes to 52 high school students in rented rooms in the Lincoln Elementary School. Prior to that date, students of school age in Niles Township had to travel to one of four area schools: Evanston, Maine, New Triet, or Carl Schurz in Chicago.

The Niles Township High School District (Number 219) was formally established in 1936. One of the original school board members, Armond King, helped to acquire the land from the Cook County Forest Preserve district for the sire of a new high school building. Built for less than a million dollars, and funded by Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Public Works Administration, Niles Township High School (now Niles East) was dedicated on April 16, 1939.

Perhaps the greatest testament to the strength of area residents during the years of the Depression were the number of institutions in the private sector that began during the 1930s. Four new churches were organized during the first two years of the Depression: the Presbyterian Community Church, the First Church of Christ Scientist, and the Central Church (Methodist Episcopal) and the Trinity Church in 1931.

In that same year, Reverend Frederick Detzer died after 50 years of service to St. Paul’s Lutheran Church. When he succeeded by Reverend Otto Arndt, English was used extensively for that first time in services. One of the last bastions of German-speaking Niles Township has passed.

As one of the better distractions from the troubled times, motion picture houses managed to hold their own during the Depression, in America in general and Niles Center in particular. Talking movies, shown for the first time in the Niles Center Theater in September 1930, became the rule by the summer of 1933.

Another remarkable legacy of the Depression is the number of civic organizations, some still in existence, that began during the years of economic collapse. Among them are the Boy Scouts, organized in 1929, and the Girl Scouts in 1930, the Cosmos Club, a women’s group that was organized in 1930 and started the village’s first public library the same year; the Community Choral Society; Niles Center Post 320 of the American Legion in 1931; the Niles Center Civic Orchestra in 1934; the American Legion Auxillary; and the SUB DEB Club in 1935. The Niles Township Unit of the American Red Cross and the East Prairie School PTA were formed in 1937, and the Niles Center Post of the Veterans of Foreign Wats and the Niles Center Rotary Club in 1939.

The ever-changing face of Niles Center was now ready to face the 1940s which would introduce an astonishing era of village growth and maturity… and even a name-change.