3 Niles Centre

THE SMALL SETTLEMENT of Niles Centre was made up of just 57 households in 1880, although the township had a population just in excess of 2,500. It was, however, fast becoming an important area marketplace around that time, the keystone of which was the area’s first farmer’s market.

For about four decades beginning in 1880, the first Tuesday and third Thursday of each month were established as market days, and merchants from as far away as the city of Chicago as well as McHenry and Kane counties came to meet with area farmers and purchase their produce. Pigs, poultry, horses and a variety of vegetables were offered for sale in large numbers on market days.

The idea for the market seems to have originated with Peter Blameuser, Jr., who had billboards printed advertising the earliest events. Nearly a century later, a 1976 brochure called Early Skokie, prepared by Roberta Sweetow for the League of Women Voters of Skokie-Lincolnwood, described the colorful market days:

“The market reached from the intersection of Lincoln and Oakton to the fork at St. Peter’s Catholic Church. “A major attraction for the children of the community, market day also attracted beggars, gypsy fortune tellers and thieves, who proved to be a challenge for the local law enforcers. “Horse trading was a vigorous activity. A dispute regarding the merits of a pair of horses would most likely be settled by a horse race through town. The usual stakes were a round of drinks paid for by the loser. “Wives often accompanied their husbands into town on market days to make sure the ‘pig money got home safely. After selling their stock, the farmers often decided to have a little fun in town before returning home. They had little trouble getting home, though, their horses knew the way!”

The soft farmlands of the area were ideal for workhorses made lame by the cobblestone streets of Chicago, it was noted by one early historian of the area. In the country fields, they would remain useful for years. They were very much a part of the village life in the late l800’s, not only in the areas of labor and commerce, but recreation as well. In addition to the races, the horses were sometimes pitted against one another in pulling contests, in which pairs of horses were harnessed to wagons loaded with gravel, their rear wheels locked by a board placed between the spokes.

The gypsies mentioned in Early Skokie usually arrived at the edge of the settlement in caravans of wagons, where they camped for an evening or two. The outdoor market brought hundreds of other strangers to the area, too, including many merchants from Chicago, establishing Niles Centre as a true center of commerce.

The improvements on what is today Lincoln Avenue and the railroad through Morton Grove did much to open up travel between Niles Centre and Chicago. Still, in 1880, the settlement was overwhelmingly Germanic. According to the 1880 census records, which included the place of birth for heads of each of the 57 households in the settlement, only one household head was from England, one from France, two from Denmark, one each natives of Illinois and Wisconsin, and five were second generation offspring from area settlers. The other 46 household heads had been born in Germanic states, 21 from Prussia, seven from Mecklenburg, five from Bavaria and the remainder from other assorted Germanic areas.

In 1880, merchants John W. Brown and Samuel Meyer, the latter the son of early settlers Nicholas and Elizabeth Meyer, bought George Klehm’s dry goods, saloon, and grocery business. The store provided a wide variety of goods and services, living up to the slogan, “doing everything for the farmer that the farmer couldn’t do,” including the drawing up of wills.

Saloons

The six saloons in Niles Centre in the mid 1880s were a concern to the neighboring settlements. According to Early Skokie, the League of Women Voters brochure published in 1976, “Evanston, our neighbor to the east, and dry as a bone, made us a missionary target. They labeled our village ‘the rising hell hole.’

“Every Sunday the good missionaries would arrive here singing such hymns as ‘THROW OUT THE LIFELINE, SOMEBODY IS SINKING TODAY.’ They were an impressive sight on their horse-drawn buggies and excited children gathered about to watch. The missionaries used the old Fairview School for services, establishing it as the first English-speaking Sunday school in Niles Centre.

“Dismissing the warnings of damnation, the saloons remained open to serve our thirsty inhabitants. Equally thirsty were the many residents of Evanston, who not only helped to support our six saloons in ‘84, but were great contributors to our prohibition speakeasies in the 1920s. Our relationship with Evanston was reciprocal. They bought our booze and we bought their water.”

By 1884, the 250 residents of Niles Centre were served by the Fairview School, two meat markets, two blacksmith shops, three greenhouses, three churches, five stores and six saloons.

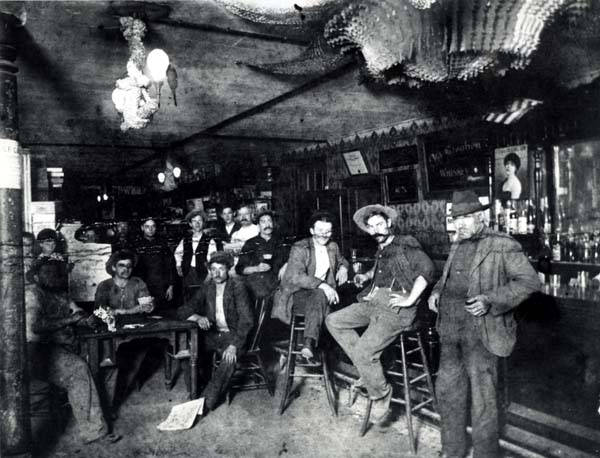

The saloon in the Klehm Brothers store, ca 1900

The saloon in the Klehm Brothers store, ca 1900

Hints of Modern Times

The years leading up to the incorporation of Niles Centre brought still more changes to the area. The first telephone in the township was installed, probably in 1885, at a toll road station west of Wilmette. On September 15 of that year, the Chicago telephone directory carried a listing for “Niles Centre, Ill.” By 1886, a second telephone was installed in the home of Henry Harms. The Chicago directory now included the following entry:

“Niles Centre, Ill.

“Henry Harms, res ……25¢”

It was some time before Harms was able to call anyone else in the settlement. Not until December 30, 1891, was another phone installed, this one in the home of George C. Klehm.

The same year that Harms got his telephone (and apparently was able to make a call for the same price as one from a pay phone today), Hermann Gerhardt came to the area and opened a blacksmith shop, possibly competing with the one operated by Peter Baumhardt and another run by Fred Schoening.

Competition for business between the Baumhardt and Schoening establishments had been sufficiently intense to prompt the owners to take part in a public contest. According to an old story, the two men vied for the title of top Niles Centre blacksmith in a contest as to who could make the most horseshoes in a day. Starting at dawn and working through the afternoon, the two men heated and hammered the shoes without pausing. When the contest was over, Schoening was declared the winner by a margin of a single horseshoe.

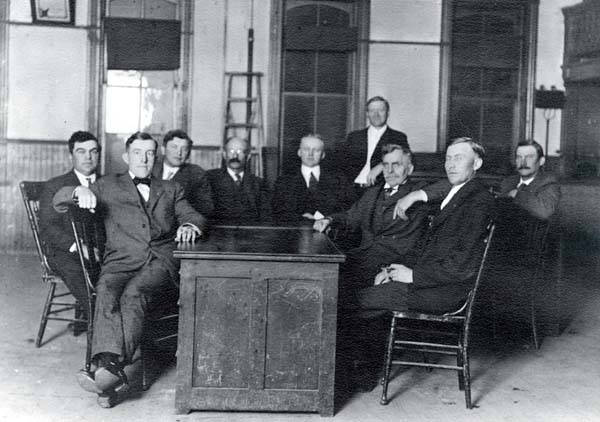

A Niles Center Village Board of Trustees meeting in the old firehouse, sometime between 1919 and 1920. Members, seated left to right: Christian Blameuser, Robert Hoffman, Albert Lies, Samuel Meyer, George H. Klehm (Mayor), John W. Brown Sr., Richard Kruse, Charles Langfield (Clerk); standing is an unidentified legal or engineering consultant

A Niles Center Village Board of Trustees meeting in the old firehouse, sometime between 1919 and 1920. Members, seated left to right: Christian Blameuser, Robert Hoffman, Albert Lies, Samuel Meyer, George H. Klehm (Mayor), John W. Brown Sr., Richard Kruse, Charles Langfield (Clerk); standing is an unidentified legal or engineering consultant

Niles Center Incorporates

Written evidence is sparse, but it was probably the old Volunteer Fire Company No. 1 that summoned the organizational impetus needed to develop the settlement known as Niles Centre into a legally certified village in 1888. The initial officers of the village— Board President Adam Harrer, village clerk Frank Wagner, and police magistrate Andrew Schmitz— were all members of the fire company when it was incorporated back in 1884. In addition, five out of the six original members of the Board of Trustees were also members of the volunteer fire company at the time of its incorporation.

In 1887, just a year before the village was incorporated, Fire Company No. 1 moved out of its headquarters in the store once owned by George C. Klehm and now owned by Samuel Meyer and John Brown, and into a new firehouse which had been built that same year. The 1887 building still stands at 8031 Floral Avenue, and since 1982 has been the home of the Skokie Historical Society.

Just as they did in earlier headquarters, social and civic functions seemed to have played an important role in the daily activities at the firehouse. Parties, dances and later school classes taught by Alma Klehm, among others, were conducted on the upper floor of the building. Meetings of the Catholic Order of Foresters, the Plattdeutsch Guild, and the German Singing Club were also held in the fire station.

On March 6, 1888, presumably after many discussions at the new firehouse, an election was held in the same building on the question of whether to organize as a full-fledged village. Of the total of 58 votes cast, 41 were in favor of incorporating as a village, 16 were against incorporating as a village, and one was against incorporating in any form whatsoever.

A little more than a month later, on April 17, elections were held at the firehouse to determine the village’s first officials. As required for village government by Illinois law, the offices of Board of Trustees, President of the Board, Village Clerk and Police Magistrate were created.

Adam Harrer defeated Herman Schiller 40-1 to become the first President of the Board of Trustees, essentially becoming the first mayor. All the other elections were miniature landslides as well, a number of losers tallying only a single vote, presumably their own. Frank Wagner won the election for the office of Village Clerk, and Andrew Schmitz became the first Police Magistrate. The members of the Board of Trustees were Fred Stielow, Christian Baumann, Peter Blameuser, Jr., Fred (Fritz) Rose, Michael Harrer, Sr. and Ivan Paroubek, one of the village’s early harness makers.

While the village board was organizing and deciding on its first formal steps, it met four times in two weeks before settling down to a once-a-month schedule. During the first meeting on April 23, the winners from the March election were sworn in by Justice of the Peace George C. Klehm and results of the official canvas were recorded.

At the second meeting, lots were drawn to determine which board members would serve one-year terms and which would face re-election the following year. Trustees Michael Harrer and Ivan Paroubek submitted a draft of the board’s rules of order, which were unanimously approved by voice vote. Apparently anxious to see that the business of the village progressed despite the budding careers of more than a half-dozen newly-elected politicians, authors Harrer and Paroubek included the following stipulation in the proposed rules: “No member shall speak more than twice nor longer than five minutes on the same question without leave of the Board.”

Six standing committees were also established at the second meeting: Finance; Judiciary and Ordinances; Village and Township Relations; Streets, Sidewalks and Culverts; License and Markets; and Police and Street Lighting. The trustees also ruled that a two-thirds majority would be needed on the board to vote in favor of any action costing more than $50.

The third meeting, held on April 30, was devoted almost entirely to the subject of improving the new village’s streets, a prime concern of nearly every area resident. The village’s first ordinance, relating to roads, was passed at that meeting. Handwritten minutes of all the earliest board meetings are still on file in the Village Clerk’s office on the first floor of the Village Hall.

The famous old firehouse on Floral Avenue, now restored to serve as headquarters for the Skokie Historical Society

The famous old firehouse on Floral Avenue, now restored to serve as headquarters for the Skokie Historical Society

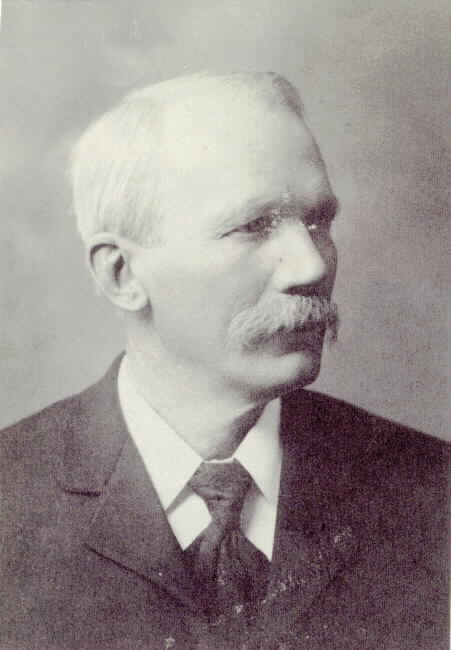

George C. Klehm (1839-1927)

George C. Klehm (1839-1927)

Alma Elizabeth Klehm, before 1900

Alma Elizabeth Klehm, before 1900

Dr. Amelia Louise Klehm (1870-1941) in the carriage in which she used to make house calls

Dr. Amelia Louise Klehm (1870-1941) in the carriage in which she used to make house calls

The Unsolved Murder of Amos Snell…

In the three decades since he had built a log cabin near the southwest corner of the original boundary of Niles Centre in 1857, Amos J. Snell had been a busy man. Acquiring hundreds of acres of land now on the north side of Chicago, he made a fortune selling timber to the new railroads and then garnered even more income by using the land he cleared to construct crude cabins to sell to new arrivals in the area.

Snell bought the Northwest Plank Road (Milwaukee Avenue) from a settler named Gould even though it was already beginning to suffer the fateful demise of all plank roads. In time, Snell rebuilt the entire road, however, using a gravel surface much more resistant to the ravages of time, and extended it northward to Wheeling. He also added a number of new tollgates, including one at Fullerton, Belmont, Jefferson and Leland Avenues. By the 1880s, each of these tollgates could take in $400 or more on a busy day. On some Sunday afternoons the gate at Fullerton collected more than $700, its coffers swelled with tolls from picnickers and visitors to the new cemeteries established north (in those days) of Chicago.

“One night in 1888,” Bertha Rosche wrote in her manuscript, Setting Down the Record …, “Snell was murdered in his home. Clues were few, and suspicions were many. It had appearances of being an inside job. A nephew, Willie Tascott, became the prime object of the search. Detective work spread through the nation, and trails were picked up in Europe. The case dragged on and all leads faded out. Neither Tascott nor other suspects ever were caught.”

The motive for the crime was never discovered, but it is known that many users of the toll roads in northern Illinois were becoming increasingly resentful of the fees they were compelled to pay for driving wagons on private roads. Complaints were many, as were attempts to dodge the toll by driving around the tollgates. Whether the culprit was Willie Tascott or a disgruntled toll-road traveler remains a mystery.

Early Village Ordinances

It was at the fourth meeting that ordinances establishing the real legal character of the new village were adopted. At the meeting of the Niles Centre Village Board, held at the firehouse on May 8, 1888, the trustees passed 10 ordinances. Covering some 15 printed pages, they were published in booklet form with a few additional laws the following year by the Chicago printing firm of Holton & Furbush. The booklet, now a century old, still exists. So that area residents could see the new ordinances more quickly, copies of the laws were also printed individually and posted in a number of different public locations, one at the post office, another at Meyer and Brown’s store and a third at the saloon of Ludwig Schmitz.

The first of the ordinances passed during the May 8 meeting, Ordinance No. 2, established the boundaries of the new village in terms only a surveyor could love:

“Section 1. That the boundaries of the village of Niles Centre area hereby declared to be and are hereby established as follows, to wit: The said village of Niles Centre shall embrace the East three-fourths (3/4) of the North one- fourth (1/4) of Section Twenty-eight (28), the East three-fourths (3/4) of the south one-half (1/2) of Section Twenty-one (21), and the East three-fourths (3/4) of the South one-half (1/2) of the Northwest quarter (1/4) of Section Twenty-one (21), situated in Township Forty- one (41) North Range Thirteen (13). East of the third principal meridian, in the County of Cook and State of Illinois.”

During the 1820s and early 1830s, U.S. land surveyors had worked northward through Illinois, dividing the land into enormous squares with range, township and section lines. Prior to the development of extensive road networks for automobiles during the first two decades of the 20th century, township and section lines were prominent figures on most large-scale maps.

The borders of the original village, drawn up along fractional section lines, coincide with present-day Main Street on the north (except for the northwest corner, which is marked by Laramie, Greenleaf and Linder), Long Avenue to the west, Mulford Street on the south, and Skokie Boulevard to the east, encompassing an area of just under one square mile. The northwest corner of the original village was expanded at the time of incorporation to include the cemeteries of St. Peter’s and St. Paul’s Protestant churches. Several large annexations, increasing the area of the town more than tenfold, were made in the 1920s.

In addition to Ordinance No. 2, establishing the boundaries of the village, a number of other laws were passed during the meeting of May 8, 1888. Among the more notable were proscriptions against various forms of misbehavior, an ordinance prohibiting livestock from running at large within the village limits or being staked along any village street, a law controlling dogs, and the establishment of a wide variety of licenses.

The license for a dram shop required the hefty fee of $150 plus the posting of a $3,000 bond payable to the state. Peddlers of food and other staples could acquire a license to sell their goods within the village limits, with fees averaging $10 a year. The carefully worded ordinances, undoubtedly patterned after those in other municipalities, helped to give the village a solid legal foundation, but growth, nevertheless, came slowly.

A Lively Decade

The 1890s began riotously. Early in May 1890, a group of farmers disguised as Indians attacked the tollgate, then owned by the heirs of Amos Snell, on Milwaukee Avenue at Fullerton. Angered that the Cook County Board had not taken fast action on their complaint made April 28 over high fees for the toll road, the ersatz Indians chased away the toll keeper shortly after midnight and burned his house and the tollgate to the ground. When police arrived, they did nothing to stop the mob, apparently sympathetic with their views.

The event to the south had an immediate effect on the residents of Niles Centre. Shortly after the attack, Cook County purchased the rights to Milwaukee Avenue from Amos Snell’s heirs, and those to Lincoln Avenue from Henry Harms. Although a single tollbooth remained on Milwaukee Avenue as late as 1892, the entire toll-road system was then abolished by the county. Both roads, once plank roads and later gravel roads, have remained public property ever since. But there is evidence that the county had as much trouble maintaining the roads as private owners had in earlier years. Testimony to that fact is found in this recorded anecdote. Near the end of the decade, in 1899, George H. Klehm stood for a week on Lincoln Avenue asking every passing teamster to haul a load of gravel to improve the road, which was sometimes nearly impassable to Chicago. In addition to 30 loads of broken bricks donated by two area brickyards to use as road fill, Klehm finally succeeded in getting 169 loads of gravel hauled free.

The whole subject of roads became increasingly important throughout the decade. Around 1892, two village residents, John Noesen and slightly later Henry Heinz, became the first area owners of motorcars. Without a single paved road in the village or the county, early automobile trips had to be at the least joltingly adventurous.

The unpaved roads of Niles Centre, especially those north of town, passed by the village’s many saloons, which became the focal point of yet another controversy during the l890s. Back in the l850s, Dr. John Evans, for whom Evanston was later named, began buying land for the new Northwestern University. In 1855, eight years before Evanston was incorporated, the university’s charter was altered to forbid the sale of alcohol within four miles of the campus, a restriction that was not rescinded until 1971. Niles Centre’s saloons, just outside the four-mile boundary, became tempting spots for Northwestern students seeking a liquid escape from the pressures of college life.

About a half-dozen other saloons were located in an area just northeast of Niles Centre to the little settlement of Grosse Point, later annexed to Wilmette. Although these watering holes were clearly less than four miles from the Northwestern campus, an 1866 court case determined that they were legal because the trip to them over existing roads was more than the minimum legal distance. But by 1893, new roads now placed all the saloons within a four-mile hike from the campus. Members of Evanston’s Citizens League used an early Rand McNally map to argue against the continued operation of the offending saloons; those in Niles Centre proper, however, escaped the Evanstonians’ legal pressure.

The neighboring village of Morton Grove was incorporated in 1895 and Niles, formally known as Dutchman’s Point, in 1899. The still strongly Germanic roots of Niles Centre and its neighbors is illustrated by a three-day convention held by the Plattdeutsch Guild in Morton Grove’s St. Paul Park, owned by George C. Klehm. Thousands of people of Germanic stock from the settlements north of Chicago came to the three-day affair, some, it is recorded by Dampfross (steam horse), others by Stahlross (steel horse or bicycle).

George C. Klehm had built St. Paul Park on land that is now part of the Forest Preserve District. Klehm dammed the North Branch of the Chicago River, making a lake large enough for picnickers to enjoy riding in the boats that he supplied, and built a pavilion where dances were often held. Many people regarded the park as the most beautiful spot in the Chicago area, and it was always a popular picnic area for Niles Centre residents.

The village of Niles Centre was governed relatively uneventfully throughout the l890s. John W. Brown, whose father, with Samuel Meyer, bought and operated George C. Klehm’s store, served as the second mayor from 1890 to 1895. After Peter Blameuser, III, served a single term, George Sintzel was mayor for nearly 13 years, from 1897 until his death in 1909. George H. Klehm succeeded him as mayor, remaining in office from 1910 to 1922.

During the final years of the 19th century, the neighboring towns along Lake Michigan grew quickly. Even by 1890, the population of Evanston had grown to more than 13,000. In its first full decade as an incorporated village, Wilmette more than tripled its population, growing from 419 residents in 1880 to1,458 in 1890. By the year 1900 the population of Niles Centre was 529, growing slowly to just 568 ten years later. Other inland neighbors also grew more slowly than the towns along the lake. In the census of 1910, Niles, still often called Dutchman’s Point, had a population of 569, one more resident than Niles Centre.

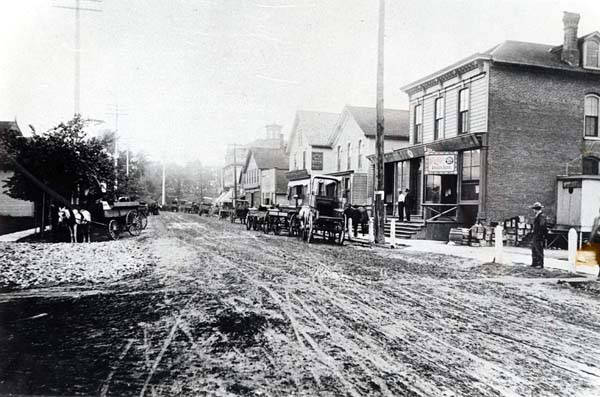

Muddy Lincoln Avenue, looking south from St. Peter’s Church, about 1890

Muddy Lincoln Avenue, looking south from St. Peter’s Church, about 1890

A Turn-of-the-Century Town

In 1900, Niles Centre was still a tiny village amid rapidly growing communities to the south and east. Best known at the time for its market days, truck farms, greenhouses and saloons, it was still small enough so that just about everyone knew everyone else. Many of the inhabitants were related, the overwhelming majority still of German origin or descent.

There were still no paved roads. Early photographs show deep ruts on the main streets such as Harms Road (now Oakton), Main Street, Back Street (now Floral Avenue), Lincoln Avenue and Market Street (Warren Avenue). The going must have been tough enough for horses and mules, and nearly impossible for the earliest motorcars.

Landmarks of the downtown area were the two large buildings at Lincoln and Oakton, one a store operated by Edwin and George H. Klehm, the other the large Blameuser Building. The Klehm brothers’ store had been built by Henry Harms, purchased by George C. Klehm, then by Samuel Meyer and John W. Brown. Edwin and George H. Klehm brought the store, which still contained the little post office, back into the family, however, when they repurchased it before the turn of the century.

Both the Blameuser Building and the Niles Centre Hotel, the latter built sometime before 1890 by Henry Harms, contained popular saloons. At the time, the hotel building was leased by early village trustee Fritz Rose. His name appears prominently on an exterior wall in an old photograph.

The spacious home of Edward T. Klehm, built in the year 1900 at 5144 Oakton, had the distinction of being the first building in the village to have indoor toilet facilities. A windmill behind the house pumped water from a well into the house.

The year 1900 brought other signs that times were beginning to change for Niles Centre. For the first time, English replaced German during services at St. Peter’s German Evangelical Lutheran Church.

In the same year, the first public school building, named Niles Centre School, opened within the village limits. The four-room, two-story brick schoolhouse was located at the present site of the Skokie Post Office, where it continued to serve the village’s children until about 1927. Vacant for some time, the building was finally torn down in the 1930s. For two years after it first opened, young Alma Klehm taught in the Niles Centre School.

As the twentieth century got underway, the village, and the farmlands around it, were particularly characterized by the dozens of greenhouses and vegetable farms that flourished in the area. During those early years of the 1900s, the Stielow brothers, advertising “All Kinds of Cut Flowers,” operated two large greenhouse complexes. Ludwig Schmitt and E. H. Blameuser grew carnations, the latter calling his operation a “Grower and Shipper to Wholesale Commission Houses.”

There were many other flower and vegetable growers, as well as various small industries which sprang up to serve them. George W. Mittlestaedt for example, advertised “Hotbed Windows and Glass,” as well as “Farm and Greenhouse Boxes.” Edwin T. Klehm and many others sold seeds. The Niles Centre Mercantile Company, operated by George Busscher, Jr., Anthony Paroubek, and John E. Brown, sold a variety of products designed for flower growers and truck farmers. As late as 1930, an aerial photograph of the Niles Centre area shows dozens of greenhouses scattered throughout the vicinity.

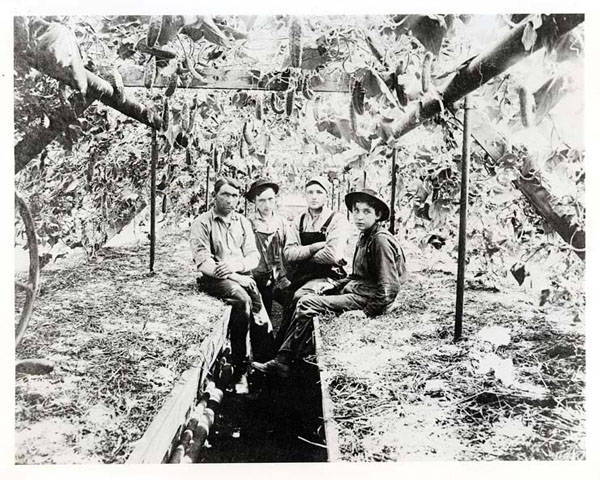

Inside the Hermes family greenhouse at 9801 Gross Point Road, about 1907. Left to right: Nick Hermes, Paul Hermes, John Goedert; the youngster on the right is unidentified

Inside the Hermes family greenhouse at 9801 Gross Point Road, about 1907. Left to right: Nick Hermes, Paul Hermes, John Goedert; the youngster on the right is unidentified

Turn-of-the-Century Neighborhoods

A neighborhood north of the original boundaries of Niles Centre could easily have become a town itself, but instead was annexed to the village in the 1920s. Sharp Corner, as it was known, developed around the sharp-angled intersection of two roads, Gross Point and Kenton (the continuation of Niles Center Road) and, as a loosely-defined neighborhood, also included the intersection of Gross Point and Golf and environs north to present-day Old Orchard Road.

Today’s Sharp Corner School was built in 1897 and greatly expanded in later years. An old map dated 1876, however, shows the location of the original frame school at Sharp Corner across the street from the present building. In the 1920s, Sharp Corner School was a two-room building, heated with a pot-bellied stove and dimly lighted with kerosene lamps. When parents traveled to the little building in the evening for meetings, they often brought their own lanterns for additional light.

The area was also known for the Farmer’s Exchange, a general store and tavern. At a 1980 meeting of the Skokie Historical Society, Bernard Hohs, the son of the Exchange owner, recalled some of his father’s activities: “He ran the tavern and also had a beer distributorship there and had a delivery. He served both Grosse Point (now Wilmette) and also Evanston. I recently saw a copy of the Evanston Review where they were reviewing the Board minutes of long ago. In one of the minutes, people were complaining about the prizefights and the gambling that were going on at the Farmer’s Exchange. That was before my time, but I wouldn’t doubt it a bit.”

Sharp Corner also had a fire department somewhat later, with a Model T Ford and some fire equipment which was believed to have been purchased in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Among the members of the Sharp Corner Fire Department were two Niles Centre trustees, Henry Vogt and Peter Conrad, as well as Fred Hartung, an early Niles Centre policeman.

Two well-known taverns were on opposite sides of Kenton at Grosse Point. One, known for a time as The 19th Tee, was owned by Bernard Hohs’ father Peter Hohs, and was later renamed The Totem Pole and still later Duffy’s. The tavern on the opposite side of Kenton had many names, including the Green Parrot inn, Sharp Corner Country Club, Sharp Corner Inn, and Ma Schramm’s.

Like Niles Centre, the Sharp Corner area was largely populated by greenhouse operators and truck farmers. On October 8, 1982, the Skokie Historical Society placed a historic marker near the sharp intersection to commemorate the old neighborhood, which had, in its entirety, been brought within the boundaries of Niles Centre in the annexations of 1924, 1925 and 1926.

Another thriving neighborhood around the turn of the century was located along East Prairie Road, an old Indian trail now a part of Skokie, but in those days east of the village limits of Niles Centre.

The focal point of the area was the East Prairie School, which had operated in the 1880s as a one-room schoolhouse. In those early days, youngsters walking to school often had to jump ditches because the boards crossing them had washed away. Like most of the Sharp Corner area, East Prairie became part of Niles Centre during the large annexation of 1924.

Sharp Corner’s famed Farmers Exchange was one of the many saloons at the north end of the village, situated on the southwest corner of Golf and Gross Point Roads

Sharp Corner’s famed Farmers Exchange was one of the many saloons at the north end of the village, situated on the southwest corner of Golf and Gross Point Roads

Dr. Amelia Louise Klehm

A number of Niles Centre’s most prominent citizens were among the six children born to George C. Klehm and his first wife, the former Louise Harms. Amelia Louise Klehm, born in 1870, began her career in the medical profession as a nurse, volunteering for duty in the Spanish-American War and caring for wounded soldiers in Florida. After the war, she studied at Chicago’s College of Physicians and Surgeons and later traveled to Europe to study in Berlin and Vienna before returning permanently to Niles Centre. Dr. Klehm seemed to prefer the name Louise, often signing her name “A. Louise Klehm’

Around the turn of the century, she opened her first office in the back of the family store at Lincoln and Oakton, later moving to the Klehm homestead at 8212 Lincoln. Regardless of the location of her office, she often made house calls, traveling in a horse and buggy and sometimes on horseback to visit patients at any time of the day or night and in any weather. Her fee for delivering a baby was $15.

At one point in her career, Doctor Klehm became a target of the Black Hand, a terrorist group emigrated from Sicily and associated with the Mafia, which was active in the United States in the early 20th century. Although the specifics are not recorded, the gang undoubtedly followed its usual method of extortion by sending her a letter, complete with the image of a black hand, demanding that a specified amount of cash be delivered to a designated location. She never gave in to the threats of the gang, but for some time her sister, Alma, rode about town with her, carrying a loaded revolver at the ready.

In addition to serving the residents of Niles Centre, she was also on the staff of St. Francis Hospital in Evanston, where her name is honored on a plaque in the lobby. On her deathbed in 1941, Doctor Klehm destroyed her patients’ unpaid bills. Skokie’s Louise Avenue is named after this pioneering doctor.

Dr. Amelia Louise Klehm can lay claim to being one of the first physicians to set up practice in Skokie (then Niles Centre)

Dr. Amelia Louise Klehm can lay claim to being one of the first physicians to set up practice in Skokie (then Niles Centre)

Alma Elizabeth Klehm

For many years during the middle decades of the 20th century, Alma Klehm was the oldest lifetime resident of Skokie. She was also a guiding force in the civic and cultural life of the village for many years.

Born in 1876, the youngest of George and Louise Klehm’s six children, her mother died before she was three years old. In 1881 her father married Eliza Ruesch with whom he had six additional children. Alma became one of the first youngsters in the area to attend high school. She rode a bike or walked to the Morton Grove station and took the train to Chicago’s Mayfair High School (later renamed Carl Schurz High School). Following her graduation, she passed a state examination qualifying her to teach grades 1-8.

In December 1899, she joined two other teachers on the second floor in the firehouse on Floral Avenue. When the Niles Centre School opened a few weeks later, she moved there, remaining for two years. In 1902, she moved to the old Fairview School, known at the time as the South Niles Centre School, where she taught for 14 years before returning for three more years at the Niles Centre School. After 19 years of teaching, Alma Klehm was forced to retire because of polio, which left her unable to stand for long periods of time.

Alma lived in the village her entire life, except for a period of three years when she tried homesteading in the state of Washington. There she learned how to use a revolver to scare off threatening Indians, a skill she felt fortunate to possess later when her sister was threatened by the Black Hand gang. In addition to her work as a teacher, Alma served as Niles Township Treasurer, a bank director and a charter member of the Niles Centre Woman’s Club when it organized in 1926, becoming its president for the 1932-33 term.

In 1962, at the age of 86, she was named “Calendar Girl” by the First National Bank of Skokie. Her “pinup picture,” showing her reading to a young boy, was so popular that the press run had to be doubled for a total of 60,000 copies. The bank was still unable to fill all requests it received for the picture. Alma spent her last years visiting friends and relatives across the United States and working around her home. She died in 1974 at the age of 98.