1 Origins

IN THE YEAR 1831, Andrew Jackson was still in his first term as the seventh President of the United States, presiding over its then 24 states and approximately 13 million citizens. It was during that year a fur trader from England named Joseph Curtis trekked into one of those states, Illinois, to make a small historical mark of his own.

Joseph Curtis cut down some trees from the heavily forested area along the North Branch of the Chicago River and built a log cabin on a site within the limits of the present-day village of Morton Grove. The crude cabin he erected there earned the distinction of becoming the first permanent structure built by a white settler in what is now Niles Township.

The lowland where Curtis settled was rich with oak, maple and hickory forests, but for the most part was still uninviting territory because they were intermixed with large areas of marshes and wet prairie lands. Today’s Skokie Village Hall stands in what was then dense oak/hickory forest, but Niles West High School and Old Orchard Shopping Center, among other landmarks, sit on sites that were water-filled, insect-infested prairies.

At the beginning of the 1830s, the largest non-Indian settlement in the area was Chicago, which claimed only about 150 inhabitants back then. The Indians had abandoned the immediate area in which Curtis settled. It was north of a 20-mile-wide Indian boundary corridor established in 1816 by the Treaty of St. Louis to protect Chicago, Fort Dearborn (which had been rebuilt that same year) and the future site of the Illinois and Michigan Canal. There were still Indians nearby, however, and the Potawatomi were the dominant tribe.

By 1832, a few American soldiers may have passed through the area to fight in the Black Hawk War, named for the chief of the Sauk Indian tribe, whose initial skirmishes had taken place the previous year. A history of the Niles Township area written by the members of the Niles Centre Maennerchor (translated as Men’s Choir) includes the following comment: “Every white person in Northeastern Illinois fled to the barracks of Fort Dearborn at Chicago or joined the state militia to fight Black Hawk’s band.”

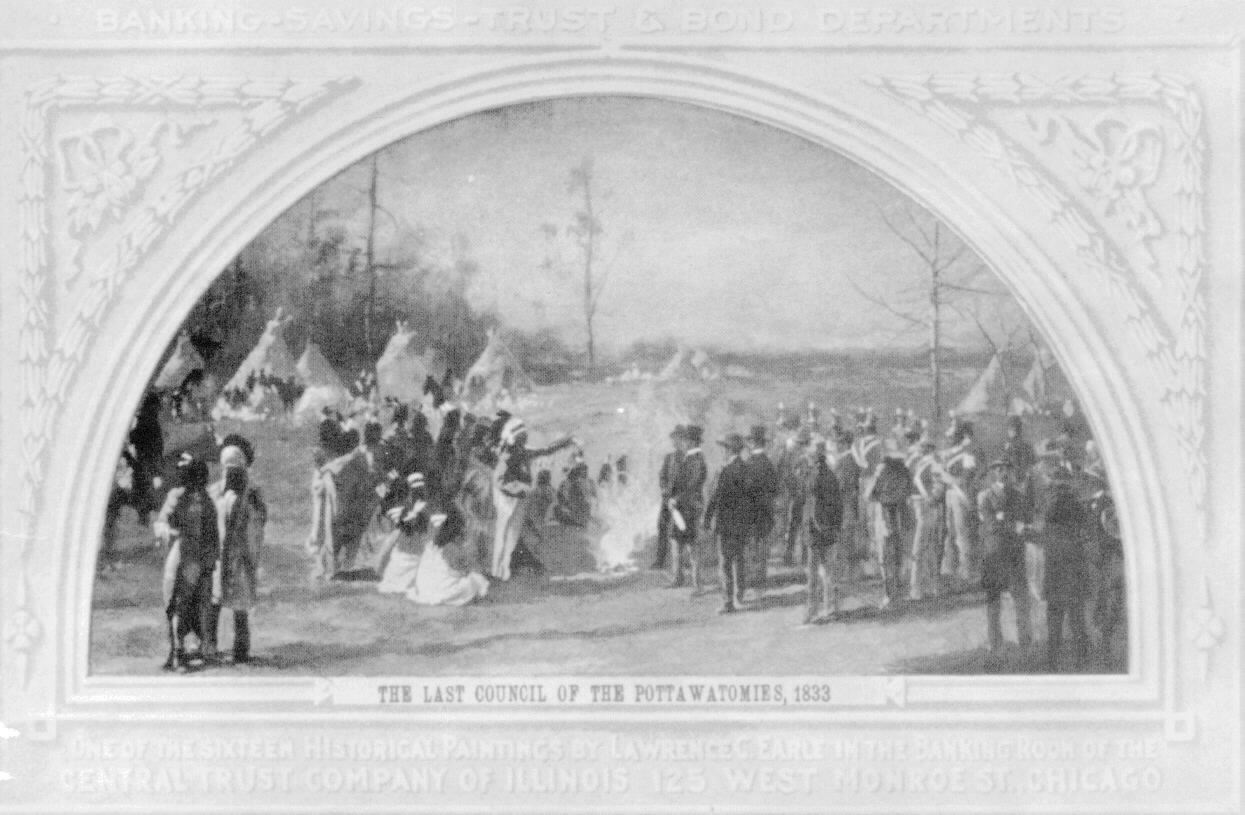

The brief war was the last of the Indian battles in Illinois. Through a formal treaty in 1833, the same year that the town of Chicago was incorporated, the three most prevalent tribes, the Potawatomi, Chippewa and Ottawa, surrendered all their lands in Illinois and prepared to move west of the Mississippi River.

That same year, John Dewes, another transplanted Englishman, built a residence about 800 yards north of Joseph Curtis, becoming the second resident of the Niles Township area. Of more lasting importance to the development of the area, however, was an act of the U.S. Congress, passed in 1833, to begin improvements on Chicago’s harbor.

The port of Chicago was hardly a well-known landmark by 1834 when a ship sailing on Lake Michigan attempting to locate it became lost in a storm. Aboard that ship was another English immigrant, John Jackson Ruland. The ship eventually dropped anchor near the present site of downtown Evanston, about 10 miles north of Chicago’s harbor.

Ruland debarked and began trudging westward through the swamps. The first ridge of higher dry land he encountered was what is today Ridge Avenue in Evanston. Continuing west across land named East Prairie by later settlers, Ruland eventually encountered more swamps which stretched until the next dry ridge, today’s Niles Center Road. From there it was a short jaunt for Ruland to the present site of Lincoln Avenue, a heavily traveled Indian trail at that time.

J.J. Ruland crossed, but chose not to settle in, land that is today within the boundaries of Skokie. The land that he found there was filled with wildlife, but equally saturated with swamp lands and other watery impediments to homesteading. At the time, buffalos, bears, panthers, deer, wildcats, and foxes roamed the grasslands and forests. Minks, otters, beavers, ducks and geese were easily found in and around the streams and marshes. Prairie chicken and quail were plentiful as well. Wild fruits and berries grew in abundance. Early settlers of the area reported that wild oranges flourished as late as the 1880s in the area along today’s Lincoln Avenue.

Ruland eventually arrived at a sand and gravel bank within the present boundaries of Morton Grove, just northeast of where the Milwaukee Road tracks cross Oakton Street near Skokie’s westernmost border. There he stopped and built a dugout shelter. The area began to take on the vestiges of a true settlement with the building of several other houses, by Jules Perrin and John Schadiger in the area along the North Branch of the Chicago River in the southwest corner of present-day Niles Township.

In 1834, Christian Ebinger, who once maintained the royal gardens of King William of Wurtenberg before coming to America in 1831, built another house along the North Branch with the help of his brothers, John and Frederick. A man named John Plank moved to the neighborhood from Chicago that same year and erected still another home.

The largest landholder in the area was Mark Noble, who came to America from England in 1832 and purchased 600 acres, of which 160 were in the southern part of Niles Township, the rest in neighboring Jefferson, now a part of Chicago. He bought the land for $2.50 an acre.

J. J. Ruland, after his wife and two children joined him, left the dugout to move a short distance west to join the young settlement which was soon to become known as Dutchman’s Point (only much later as Niles). The name for this neighborhood, which consisted of an increasing number of German immigrants, is explained by the amateur historians among the 1881 Niles Centre “Men’s Choir”: “A strip or point of timber extended from the main forest on the river along the ridge on which Plank and Ebinger lived, and the Americans, who in those days generally confounded the Germans with the Dutch, named it Dutchman’s Point, by which it is known to the present day.” The confusion was probably compounded by the word the German immigrants used to describe themselves: “Deutsch.”

Wild Encounter

This encounter in the untamed environs of Niles Township is taken from a history of the area written in 1958 by Bertha M. Rosche.

But on this day in 1834 John Ruland was looking for drier land and pushed on through the dense oak and maple forest to the next ridge, our Lincoln Avenue, which was a well-trod Indian trail. . . There he called it a day’s journey and made himself a dug-out for a shelter.

There is a story that when he finished it he took his gun and started to hunt for fresh meat. He had gone only a few rods when a huge wolf rose from be hind a log close at hand. He leveled his gun and fired, then dropped it and ran for his cave. Next morning he came cautiously back to look for his gun and found the wolf dead some 2.5 feet from where he had shot him.

A story from the era hints at the hardships of pioneer life as well as the value of a good potato. Once, it was reported, J.J. Ruland and the Ebinger brothers drove an ox cart to Chicago to buy seed potatoes. After paying $1.25 a bushel for the produce (half the cost of an acre of Mark Noble’s land), it took them two days to make the return trip to Dutchman’s Point, their cart repeatedly mired in mud.

Before the first pioneers settled specifically within the present boundaries of Skokie, harbingers of civilization were already appearing in and around Dutchman’s Point. In 1834, John Miller built a sawmill on the North Branch of the Chicago River near present- day Morton Grove because the lumber business was becoming an important industry in the area. Another advance: a United States land office serving the Chicago area was opened in 1835, allowing township settlers to make legal claim for their land for the first time (an acre in Niles Township sold for $1.25, the same price J.J. Ruland paid for a bushel of seed potatoes).

By 1836, a year after the last of the Potawatomi Indians left the Chicago area, mail was delivered to Dutchman’s Point on a regular basis by a stagecoach traveling from Chicago to Libertyville along Milwaukee Avenue. But even as the stagecoach first began delivering mail to Niles Township, work was beginning on the first rail line out of Chicago. The Galena and Chicago Union Railroad, started in 1836, was the first of many lines that would make Chicago an important railroad terminus, and eventually replace the stagecoach business.

Benjamin Hall (for whom Hall Road is named) and John Marshall built the North Branch Hotel in Dutchman’s Point in 1837. By the following year, the settlement could boast the first school in Niles Township. The little schoolhouse at the intersection of present day Harlem and Touhy Avenues had at first an enrollment of only four students, the children of the Ebinger and Ruland families. And, in 1840 the first glass of whiskey was served over the bar in the first saloon opened in Dutchman’s Point, an establishment owned by Benjamin Hall and John Marshall to complement their North Branch Hotel.

Onetime Skokie inhabitants, the Potawatomi. The painting by Lawrence Carmichael Earle (1845-1921). Courtesy of the Chicago Historical Society

Onetime Skokie inhabitants, the Potawatomi. The painting by Lawrence Carmichael Earle (1845-1921). Courtesy of the Chicago Historical Society

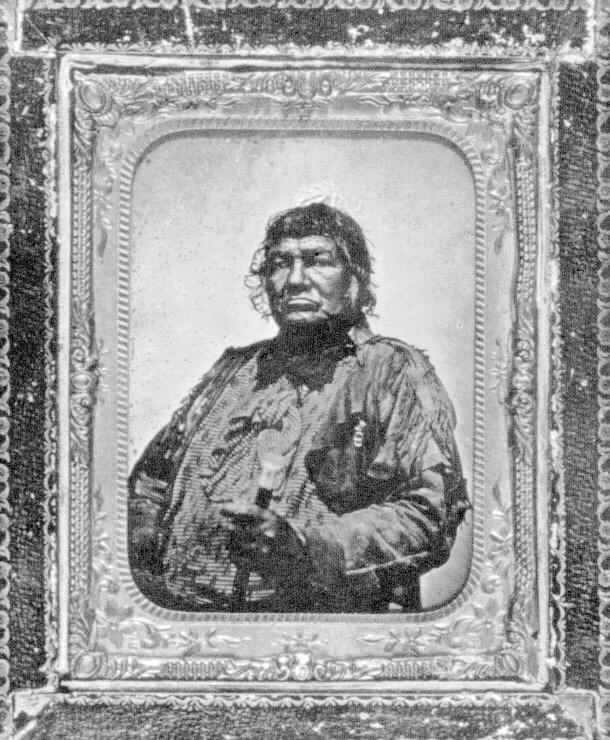

Potawatomi chief Shabbona (1775-1859)

Potawatomi chief Shabbona (1775-1859)

Indian axe head found near the corner of Golf and Knox

Indian axe head found near the corner of Golf and Knox

Ancient Ancestors

The first settlers who began moving into the present boundaries of Niles Township are described as the original direct ancestors of the modern village of Skokie, but they are far from the oldest inhabitants of the once swampy land. Ancestors much more distant arrived long ago.

Half a billion years ago the land that now comprises Skokie, as well as Niles Township, Cook County, the state of Illinois, and the entire northern United States, was at the bottom of a tropical sea. When that ocean receded about 60 million years ago, the climate inexplicably turned colder, issuing in a series of four great ice ages. The last, vast sheet of ice that covered Skokie and most of northern Illinois, was the Wisconsin Glacier, which arrived about 70,000 years ago and began to recede about 13,000 years ago.

More than anything else, the Wisconsin Glacier is responsible for the topography of most of northern Illinois. Under its mammoth weight was dragged much of the richest topsoil from the north, deposited gradually over the smoothened substrate of northern Illinois. As the glacier melted and retreated, the body of water that is now Lake Michigan rose more than 70 feet above its current level, eventually emptying east- ward through the St. Lawrence Valley and westward toward the Mississippi River through a passage at the present-day village of Summit. This area near the intersection of the Stevenson Expressway and Harlem Avenue was later the site of the famous Chicago Portage and, still later, the Illinois and Michigan Canal. Thousands of years after the Wisconsin Glacier melted into geological history, the Chicago portage allowed Indians, and later European explorers, to travel in canoes on all but a few miles from the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River, by way of the Chicago, Des Plaines, and Illinois Rivers.

At its height, Lake Michigan covered much of northeastern Illinois, including Skokie and Chicago. The Chicago neighborhoods of Blue Island and Stoney Island were two of the few areas in the vicinity high enough to remain above the surface of ancient Lake Michigan. Apparently Lake Michigan did not recede gradually to its present level, but rather in a series of relatively sudden regressions. Although he probably did not realize it, the land ridges J.J. Ruland encountered in 1834 at the present sites of Ridge Avenue and Niles Center Road were actually at different times the shorelines of old Lake Michigan. The earliest evidence of humans inhabiting land around Skokie establishes the date at about 10,000 years ago. In all probability, early Indians followed the retreating Wisconsin Glacier northward, hunting, among other game, mastodons that frequented the area. Like other cultures scattered through all of Illinois, these early Indians were Mound Builders and traces of their ancient civilizations have been found in Niles Township. A mound and some other artifacts were discovered during the 19th century along the North Branch of the Chicago River almost due west of present-day Skokie.

Indians of the Modern Era

At the time of the arrival in northern Illinois of the first French explorers, Indian culture was in turmoil. Pushed westward by the advancing European colonies in the east, Eastern Woodlands Indians, with Algonquian linguistic roots, immigrated to northern Illinois. The Indians called themselves the Illiniwek and were actually a confederation of six tribes: Cahokia, Kaskaskia, Michigamea, Moingwena, Peoria, and Tamoroa.

Allied with the Illiniwek in culture and language were the Miami Indians with large villages just south of Chicago but who ranged from Ohio through Illinois, Wisconsin and Michigan. According to reports of the earliest white explorers, the Illiniwek built long, arbor-like homes, covered with a double mat of reeds woven by squaws into rectangles as long as 60 feet. Each house accommodated eight to ten families.

Many of the Illiniwek villages were destroyed around 1680 by the powerful Iroquois, who had been expanding their territory from a base in central New York throughout the century. The virtual annihilation of the Illiniwek culture in northeastern Illinois was assured in 1769, when an llliniwek brave assassinated Pontiac, a famous chief of the Ottawa, who themselves had been displaced from their Canadian homelands in tribal and colonial conflicts. The Ottawa and their allies retaliated against the llliniwek, destroying many in fierce baffles, notably at Starved Rock, and sending the survivors fleeing to Missouri. The Miami, too, were driven out of Illinois, most settling, for a time, in Indiana.

Of the several Indian tribes that succeeded the IIliniwek and the Miami in Illinois, the most important were the Potawatomi who were closely allied with the Ottawa, especially in battles against the Miami. Even before the last of the llliniwek were driven southward, the Potawatomi were growing in power, expanding from their base near Green Bay, Wisconsin, into northern Illinois, Indiana and lower Michigan.

By the year 1800, the Potawatomi dominated the land around Lake Michigan from the Grand River on the eastern shore to the southern tip of the lake and back up the western edge to the Milwaukee River. According to the reports of some historians, the word Skokie is derived from a Potawatomi word meaning “Big Swamp.”

By the time white settlers moved to Niles Township, the Potawatomi were the Indians most likely to be encountered, although all were already under legal obligation to move westward by the Treaty of 1833. Known as the “people of the fire,” the Potawatomi were noted for their friendliness to white settlers and for their custom of inviting visitors to sit by their fires.

Near the start of the 20th century, historian Albert F. Scharf published a detailed map pinpointing the locations of Indian villages, trails and chipping stations, (where the Indians made arrowheads and tools), in Cook, DuPage and Will counties. The map shows a large village, a campground, and a chipping station located between the North Branch of the Chicago River and its West Fork, near the present-day Glenview Country Club. Another large Indian village, surrounded by numerous campgrounds and chipping stations, was shown just south of the intersection of Devon and Cicero Avenues in Chicago, less than a mile from Skokie’s present southern border.

The latter village and surrounding campgrounds were all located in a 1600-acre rectangle of land reserved in the 19th century for a half-breed Indian named Billy Caldwell. Caldwell, the son of a British army officer and a Potawatomi woman, was, at the time of his death in 1838, the chief of the Potawatomies, Ottawas and Chippewas. Caldwell’s reservation is still in evidence today as the Caldwell Forest Preserve, which follows the meandering North Branch less than half a mile from Skokie’s southwest border. Caldwell Street and the Billy Caldwell Golf Course in Chicago are also named after the old chief. Two smaller reservations, contiguous to Billy Caldwell’s land and in the southwest corner of Niles Township, were reserved for a Potawatomi woman named Victorine Potier and another woman named Jane Miranda.

The Scharf map also indicates that there was Indian activity in the heart of present-day Skokie. Four established Indian trails are shown converging near the town which is designated on the map as Niles Centre. The same map also indicates that a campground was located near the modern downtown district of Skokie.

A painting of the winter quarters in the Chicago area erected by Pere Marquette and Louis Jolliet (sometimes spelled Joliet) who passed near Skokie on their explorations of America in the 1670s

A painting of the winter quarters in the Chicago area erected by Pere Marquette and Louis Jolliet (sometimes spelled Joliet) who passed near Skokie on their explorations of America in the 1670s

![Statue of Louis Jolliet. [Reproduced courtesy of Chicago Historical Society.]](/assets/img/15b.jpg) Statue of Louis Jolliet. [Reproduced courtesy of Chicago Historical Society.]

Statue of Louis Jolliet. [Reproduced courtesy of Chicago Historical Society.]

![Skokie Marsh as it appeared to early settlers, from a photograph by Fred M. Tickerman [Reproduced courtesy of Chicago Historical Society]](/assets/img/16a.jpg) Skokie Marsh as it appeared to early settlers, from a photograph by Fred M. Tickerman [Reproduced courtesy of Chicago Historical Society]

Skokie Marsh as it appeared to early settlers, from a photograph by Fred M. Tickerman [Reproduced courtesy of Chicago Historical Society]

![Horse's jawbone found behind 8020 Lincoln, site of a blacksmith shop in the 19th century [Reproduced courtesy of Chicago Historical Society]](/assets/img/16b.jpg) Horse’s jawbone found behind 8020 Lincoln, site of a blacksmith shop in the 19th century [Reproduced courtesy of Chicago Historical Society]

Horse’s jawbone found behind 8020 Lincoln, site of a blacksmith shop in the 19th century [Reproduced courtesy of Chicago Historical Society]

Explorers Passing Through

From their earliest days colonizing the New World, the French, more than the British, held the key to exploring the vast interior of the North American continent by their control of the St. Lawrence River. The St. Lawrence offered access to the Great Lakes which, through the muddy Chicago Portage, also opened up for exploration and fur trading the entire Mississippi Valley and much of its watershed.

Although they may have been preceded by early fur traders, the first white men known to have traveled the Chicago Portage were the French priest, Pere Marquette, and a youthful explorer named Louis Jolliet. On their way back to upper Lake Michigan in 1673 after exploring the Mississippi River by way of the Fox and Wisconsin Rivers, the Frenchmen were told by the Indians about a shortcut along the Illinois and Des Plaines rivers to the great inland lake. In his journal, Marquette gave a few details of the portage, writing: “One of the chiefs of this nation (the Illiniwek) with his young men, escorted us to the Lake of Illinois (Lake Michigan), whence at last, at the end of September, we reached the bay des puantz (Green Bay) from which we had started at the beginning of June.” In his report, Jolliet also suggested the creation of a canal at Chicago to join Lake Michigan with the Mississippi.

In the autumn of 1674, Marquette returned to the Chicago area, where he remained in ill-health for the winter. Although the evidence is scarce, Marquette may well have visited the land in or near present-day Skokie during his visit to the Chicago area. A publication about the village from the 1970s mentions that the first white visitors to the Skokie area were French explorers, among whose number was Father Marquette. It is believed they arrived around 1673 and found a tribe of Potawatomi Indians living in the vicinity of a large swamp.

Subsequent use of the portage by explorers made Chicago an important link between the French colonies to the north and the Mississippi Valley. By the earliest years of the 18th century, however, the importance of the Chicago Portage began to diminish. Problems with the Fox Indians, especially around Green Bay, made travel in the area exceptionally dangerous.

Throughout most of the 1700s, the historic struggle among European nations and colonists for control of North America worsened the problems faced by explorers, missionaries, traders and settlers in the area. During the earliest years of the century, Indians fought for control of the territory around Chicago, the Potawatomi eventually emerging victorious. In 1700, the French mission of the Guardian Angel of Chicago, established just a few years earlier, was abandoned, its priests moving to safer territory. Two years later, the French fort at Chicago was also abandoned. The vacating garrison left behind a single soldier to act as a liaison between the French and the local Indians.

By 1818, Illinois attained statehood. Except for the work that year of Nathaniel Pope, U.S. Congressman from the territory of Illinois, Skokie might have eventually become a part of Wisconsin. Until his vigorous campaign in Congress, the northern border of the new State of Illinois had been envisioned to extend only to the southern tip of Lake Michigan. Pope successfully argued that the border should be moved 40 miles northward, so that the new state would have a shoreline on Lake Michigan. Today, more than half of the population of llinois, and all of Skokie, live on land added to the state as a result of Pope’s vigorous campaign.